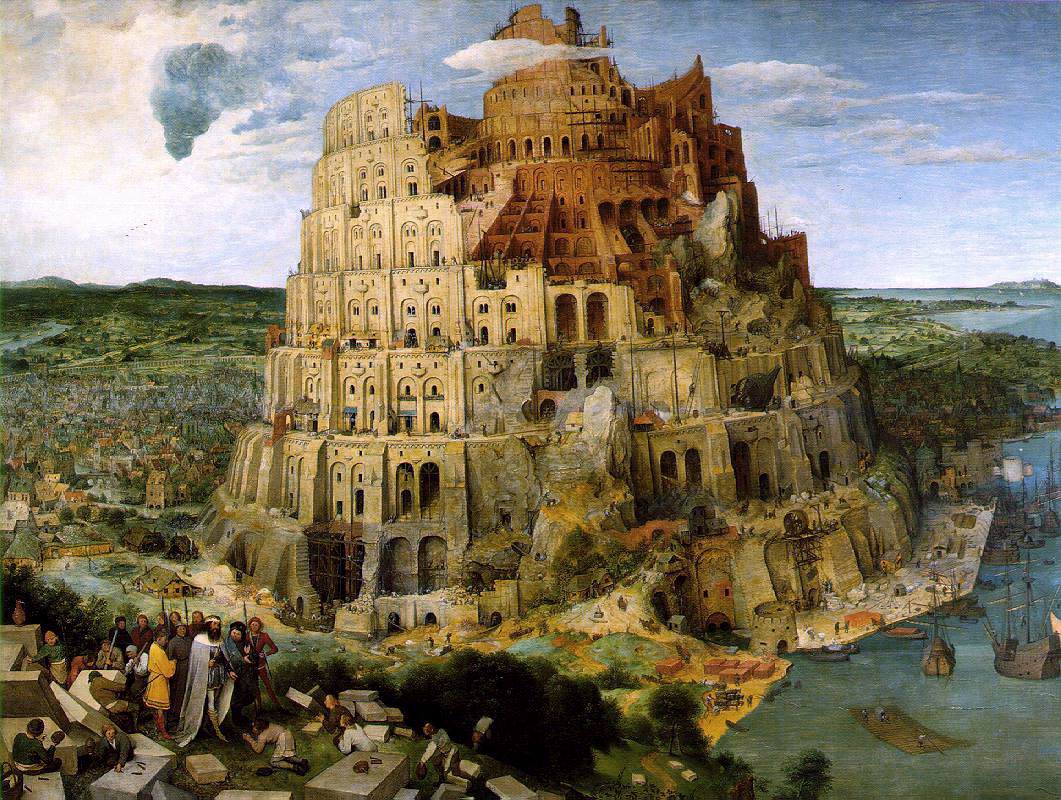

1. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525 – 1569), The Tower of Babel, 1563 (Vienna)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Extract from G. Schepers, Some Thoughts on the Role of the Human(ities) in Modern Society, Humanities 39, S. 37-41

1. The Tower of Babel

The story of the building of the Tower of Babel Tower of Babel is the one by Pieter Bruegel the Elder that is now in Vienna . It was a popular motif in Bruegel’s time. He himself painted at least one more picture with the same subject, the “little” Tower of Babel (c.1563), now in Rotterdam . But the latter, as well as the Towers of Babel by his contemporaries[1], differ from the one discussed here in a number of ways. They show the tower as a solid, well designed and impressive construction, except for the top which remains unfinished. The transport of material to the top of the construction by a broad road circling the tower is well organized. On the “little” Tower we also notice numerous cranes symmetrically placed around the tower on each storey. The Vienna version shown here gives a considerably different impression.

It is not an audacious, well designed construction that rises impressively into the clouds. Only the left side and the unfinished part at the top give an indication of this. But, at the top, one has the impression that work has stopped because the construction became too complicated and, on the left, even the foundation is either unfinished, which would be strange, or has already partly collapsed. Moreover, the whole building leans over to the left and seems to be held only by huge rocks that protrude at two places. The tower thus is not an independent, free construction but seems to be built on and around these rocks that almost reach the top. The rocks create a chaotic situation at the front part where nature and human technology are strangely mixed. Their protruding parts are still not removed and block the road circling the tower. A few scattered cranes seem hardly sufficient to move up the mass of material needed at the top. King Nimrod and the workers in the front of the picture appear almost unrelated to the tower in the background.

As a whole, the tower looks more like a huge half-dilapidated old building than a construction site. People seem to have arranged themselves within this situation and, all around the building, have built not just workers’ huts but solid houses. One has to look at the picture in its original size to discover the many almost idyllic scenes that show how the small world of human life gradually reconquers the unfinished gigantic construction of the tower. The access road to the tower is usually painted as a broad ramp with heavy traffic but Bruegel paints it as a small road over a narrow bridge and with houses squeezed in on both sides, an almost romantic scene that one would rather imagine along a lonely country road.

Much more could be said about Bruegel’s painting. Every time one looks at it one discovers new and fascinating details. The artist shows the complexity of human life and many of its diverse aspects. The traditional motif of man’s hubris and the limits set by God are reinterpreted in the context of his time. The fascinating possibilities of science and technology are indicated but also their limitations and dangers. There is the rigid despotism of the king who uses these possibilities for his own purposes without concern, it seems, for the needs of the people.[2] There are the forces of nature that can be used but not completely controlled and subdued. Even the human nostalgic longing for a return to a more natural life in the country is indicated, a tendency that became much stronger later in European history but has predecessors in Chinese Taoism or the bucolics of late antiquity. Moreover, the gigantic construction of the tower is contrasted with the small world of normal people with their needs and aspirations. The complex relations between these and other elements are shown and make the viewer aware of the deeper dimensions of human life. They point to basic problems some of which are as relevant today as they were in the 16th century.

2. The Fall of Icarus (Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1554-55)

This picture challenges even more the optimism caused by human inventions and discoveries. The former are referred to by the theme of this painting, the latter by the ships sailing out into the world. Ironically, the three persons in the picture are not at all interested in the first flight by human beings nor in its dramatic ending. The viewer, too, will need some time to find the helplessly struggling legs of Icarus sinking into the sea in front of the largest ship. The flight is not shown at all, only the fatal end of it in a corner of the picture. The three persons in the picture also appear in Ovid’s account of the story (Metamorphoses VIII, 183-235), but whereas Ovid has them believe that Daedalus and Icarus flying in the sky must be gods, Bruegel’s fisherman does not even notice Icarus’ fall just in front of him, the shepherd turns his back to the scene looking up to the sky where his Christian God resides, and the farmer in the foreground is only occupied with carefully drawing his furrows. He dominates the picture, creating a contrast between his small and peaceful world and the world of seas, harbours, and faraway lands that extends in the background.

[1] Particularly those by Hendrick van Cleve (c. 1525 - 89) and Lucas van Valckenborch (c. 1535 - 97).

[2] It is generally assumed that this is also directed against Spanish rule over the Netherlands

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, c. 1554-55