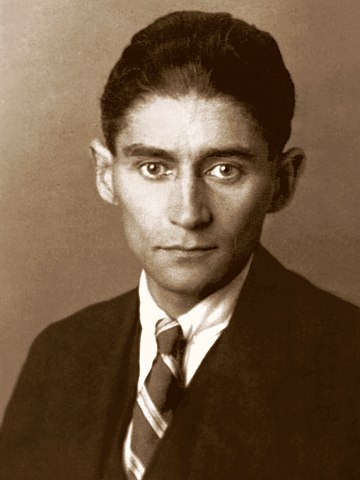

Franz Kafka was 40 years old when he died in 1924, one year after the above photograph was taken. At that time, only a few people knew and appreciated him. Today, 100 years later, people all over the world are fascinated by his works and the literature about him is immense.

Kafka's difficult relationship with his father is well known. He felt almost crushed by his overpowering personality. His relationships with women also caused additional pressure and complications. Three times he was engaged to Felice, her friend Grete followed, then his great love Milena and finally a reconciliatory ending with Dora. He found the most support with his sister Ottla. Both helped each other to get out of their father's spell. This is just a small hint that gives an idea of the immense complexity of Kafka's inner life. But we should leave the riddles of his life, which Kafka himself could not solve, as they are. The insights Kafka gained he tried to express in his texts. We should stick to those.

Kafka's willingness to sacrifice everything else in order to give expression in his literature to the "enormous world" and the "dreamlike life" he felt inside him impresses people to this day. But the texts are not easy to understand. Kafka created a whole new kind of literature to free himself from the constraints and prejudices of traditional language. Only gradually is it dawning on many that what he describes is not a grotesque, absurd, not even "Kafkaesque" world, but that he makes visible an inner truth that is obscured by our attachment to conventional thinking. (more in detail)

I remember my first Kafka reading when I was still at school. I had absolutely no idea what to do with The Metamorphosis. A young teacher tried to make us understand Up in the Gallery. The look on our uncomprehending faces must have irritated him so much that he shouted at us: "Don't you understand? Don't you understand?" Today, both texts belong to my favourite readings, in which I always make new fascinating discoveries.

How was that possible? I see two main reasons for this. One is that there are, unfortunately only a few, good publications on Kafka. The other reason is a fact I only gradually became aware of, namely the fact that our understanding of Kafka's texts grows with our own life experiences. However, I had not expected that my move to a university in Japan and the decades of new experiences there would mean such a leap in this direction. How was that possible? Kafka hardly knew anything about Japan. How could he nevertheless describe things that are very much alive in Japanese language and culture, but largely unknown and misunderstood in Europe? But isn't that precisely what art and the artist are about, the ability to make visible deep, inner, universal truths that are often not even present in the traditional world of imagination and its language?

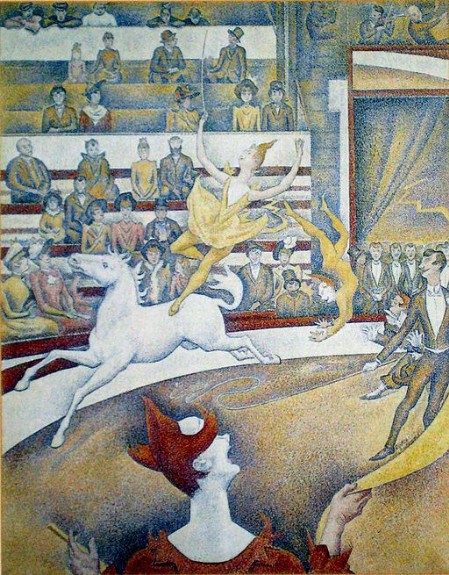

For this, a different attitude, a different approach to reality is necessary. Kafka hints at this when he initially speaks of the "immense world" in his head that threatens to tear him apart, while only a year later he speaks of his "dreamlike inner life". What this difference means to him is something Kafka illustrated especially in Up in the Gallery.

In this context, I would like to quote his girlfriend Milena Jesenská, who probably understood him better than any other person in his life.

Certainly the thing is that we are all apparently able to live because at one time or another we have fled to lies.... But he has never fled to a protective asylum, to any. He is absolutely incapable of lying, just as he is incapable of getting drunk. He is without the slightest refuge, without shelter. That is why he is exposed to everything we are protected from. ...

[Milena Jesenská to Max Brod [early August 1920] Written in Czech; translated by Max Brod].

This unconditional striving for truth occasionally even takes on almost religious dimensions with Kafka, when at the height of his creative powers (in Zürau) he speaks of only being able to have happiness "if I can lift the world into the pure, the true, the unchanging". (Diaries, 25. 9. 1917) Something of this, I think, is felt by every reader in Kafka's texts, and this fascination leads one to deal with him again and again. And how much it is worthwhile to dream with Kafka, to discover the "dreamlike inner world" in his texts, is something I have in fact often experienced and would now like to try to convey here.

Since time immemorial, human dreams have found expression in myths and legends. Kafka ties in with this when he takes up such motifs in some of his short stories. His Prometheus is particularly interesting here, especially because of the contrast with Goethe's poem of the same name. In Kafka, the whole development towards European modernity is, as it were, bent back to its pre-mythical " ground of truth".

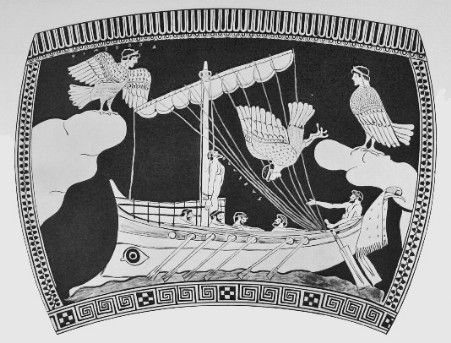

Another hero of Greek mythology, Odysseus, is at first almost ridiculed in The Silence of the Sirens with his "abundance of tricks", but then shows himself to be probably the most positive figure in Kafka's writings, who makes visible an almost utopian alternative of being human.

Particularly important for understanding Kafka's world is his short, very dense text Up in the Gallery, for which I have therefore written a separate introduction. A similar problem is addressed in the short text Der Kreisel.

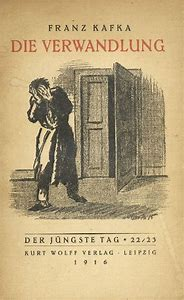

Also separately introduced is a theme that, in addition to some life testimonies, plays a central role above all in The Metamorphosis and in Kafka's last work Josefine, the Singer, or The Mouse Folk.

It is about a special form of emotional dependence. This is still hardly present in the world of German language and culture, but was nevertheless recognised and comprehensively described by Kafka as an important element in human relationships. It is explored here in a roundabout way via the Japanese language and culture, where it is known as Amae.

Finally, a particularly original expression of Kafka's "world in his head" and his "dreamlike inner life" can be found in The Bridge, a playing with the limits and possibilities of being human.

Noch im Aufbau befindet sich ein Abschnitt, in dem eine das Lesen begleitende Interpretation einiger Texte Kafkas versucht wird.

Still under construction is a section in which an attempt is made to accompany the reading of some of Kafka's texts with a simultaneous interpretation.