.

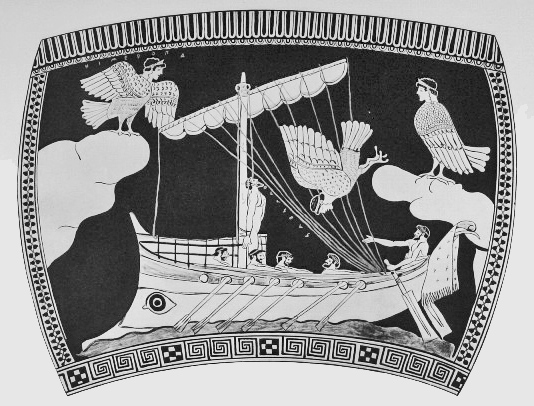

Odysseus and the Sirens. Detail of an Attic vase, ca. 480-470 B.C. From Vulci.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d3/Furtwaengler1924009.jpg

[Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente II: [2] [„Oktavheft G“] (S. 40-42)]

Beweis dessen, daßss auch unzulängliche, ja kindische Mittel zur Rettung dienen können.

Proof that even inadequate, indeed childish, means can be used for rescue.

[This first line already contains, as often in Kafka, the decisive statement, whose meaning, however, unfolds only in the following text. The classical figure of Odysseus, the man rich in guile, the man who acts wisely and thoughtfully, is radically called into question with the reference to his downright childish means. He thus seems to join the ranks of Kafka's multitude of protagonists, all of whom apparently fail in the end. Precisely for this reason, however, the word rescue is all the more astonishing here and must not be overlooked. The fact that Kafka mentions the possibility of rescue clearly sets Odysseus apart from the crowd of other protagonists].

[1] Um sich vor den Sirenen zu bewahren, stopfte sich Odysseus Wachs in die Ohren und liessß sich am Mast festschmieden. ÄÄÄÄAhnliches hätten natürlich seit jeher alle Reisenden tun können (aussßer jenen welche die Sirenen schon aus der Ferne verlockten) aber es war in der ganzen Welt bekannt, dassß das unmöglich helfen konnte. Der Gesang der Sirenen durchdrang alles, gar Wachs, und die Leidenschaft der Verführten hätte mehr als Ketten und Mast gesprengt. Daran nun dachte aber Odysseus nicht obwohl er davon vielleicht gehört hatte, er vertraute vollständig der Handvoll Wachs und dem Gebinde Ketten und in unschuldiger Freude über seine Mittelchen fuhr er den Sirenen entgegen.

To protect himself from the Sirens, Odysseus stuffed wax into his ears and had himself forged to the mast. Of course, all travelers (except those who were tempted by the Sirens from afar) could have done something similar, but it was known all over the world that this could not possibly help. The Sirens' song penetrated everything, even wax, and the passion of the seduced would have broken more than chains and masts. Odysseus did not think about it, although he might have heard about it, he completely trusted the handful of wax and the bundle of chains and in innocent joy about his little means he went to meet the Sirens.

[The first paragraph, right at the outset, completely destroys the traditional image of Odysseus with biting irony. What is the point of plugging one's ears when it is a matter of hearing the song? Even worse, the well-travelled man obviously doesn't know what all the world knows, namely that it doesn't help anyway. At this low point, however, a turn towards a positive image of Odysseus begins, which is easy to overread, if you don't know Kafka. That Odysseus "did not think of it" could mean that he overlooked something, an already somewhat toned-down criticism that fits with what has gone before. But, here comes the twist, it can also be an expression of self-confidence and strength in the sense of "I'm not considering doing that." Even more astonishing in the context of Kafka is the following complete confidence and innocent joy of Odysseus. As W. H. Sokel [n. 22] notes, "Trust, innocence and power, such is the trinity of blessings in Kafka." The fact that all three are at least hinted at here, albeit presented more like childish behaviour, sets the stage for the positive development that follows.]

[2] Nun haben aber die Sirenen eine noch schrecklichere Waffe als ihren Gesang, nämlich ihr Schweigen. Es ist zwar nicht geschehn, aber vielleicht denkbar, dassß sich jemand vor ihrem Gesange gerettet hätte, vor ihrem Verstummen gewißss nicht. Dem Gefühl aus eigener Kraft sie besiegt zu haben, der daraus folgenden alles fortreißssenden ÜÜUberhebung kann nichts Irdisches widerstehn.

But the Sirens have an even more terrible weapon than their song, namely their silence. It has not happened, but it is perhaps conceivable that someone might have saved himself from their song, but certainly not from their silence. Nothing earthly can resist the feeling of having defeated them by one's own strength, the exaltation that follows from this, sweeping everything away

[Before that, however, there is a remarkable paragraph in which Kafka revives the warlike world of the ancient heroes with his reference to the terrible weapons and the pride in one's own strength that leads to victory and to an exaltation that sweeps away everything. Even silence and the beauty of song are turned into weapons here. It is a deadly struggle. Whoever loses will be destroyed, as is said later of the Sirens. But even the victor cannot escape this fate. He destroys himself through his triumphant self-conceit.]

[3] Und tatsächlich sangen, als Odysseus kam, diese gewaltigen Sängerinnen nicht, sei es dassß sie glaubten, diesem Gegner könne nur noch das Schweigen beikommen, sei es daßss der Anblick der Glückseligkeit im Gesicht des Odysseus, der an nichts anderes als an Wachs und Ketten dachte, sie allen Gesang vergessen liessß.

And indeed, when Odysseus came, these mighty singers did not sing, whether they believed that only silence could cope with this adversary, or whether the sight of bliss in the face of Odysseus, who thought of nothing but wax and chains, made them forget all singing.

[Here the tone changes compared to the second paragraph. Only an echo of its warlike language is still perceptible in some words. But "mighty" refers only to the Sirens' song and "opponents" and "come to terms" refer rather to peaceful rivalries, such as in sport. Thus the attitude of the Sirens has already changed considerably and in the case of the second possibility they are even just full of admiration for Odysseus' bliss. He is like a child who is completely absorbed in his play and forgets everything around (like the Sirens forget their song). However, this no longer appears as childish as in the first sentence, nor as rather childish-naïve as at the end of the first paragraph, but as an inner strength in front of which even the Sirens capitulate].

[4] Odysseus aber, um es so auszudrücken, hörte ihr Schweigen nicht, er glaubte, sie sängen und nur er sei behütet es zu hören, flüchtig sah er zuerst die Wendungen ihrer Hälse, das Tiefatmen, die tränenvollen Augen, den halb geöffneten Mund, glaubte aber, dies gehöre zu den Arien die ungehört um ihn erklangen. Bald aber glitt alles an seinen in die Ferne gerichteten Blicken ab, die Sirenen verschwanden ihm förmlich und gerade als er ihnen am nächsten war, wußsste er nichts mehr von ihnen.

[Odysseus, however, to put it thus, did not hear their silence, he believed they were singing and that only he was protected from hearing it, he first fleetingly saw the craning of their necks, the deep breathing, the tearful eyes, the half-open mouth, but believed that this belonged to the arias that sounded around him unheard. Soon, however, everything glided away from his distant gaze, the Sirens literally disappeared from his sight, and just when he was closest to them, he no longer was aware of them.

[This brings us to the climax of the narrative, the encounter between Odysseus and the Sirens. The first sentence makes a final attempt to explain why Odysseus was saved. But the paradoxical statement that he did not hear the silence seems to suggest the futility of any rational explanation. The following "sheltered" is also unclear. Does it mean "sheltered from hearing it" or "protected to hear"? Whichever way you look at it, it doesn't matter to Odysseus anyway. Only briefly does he perceive the Sirens, then everything glides away from his gaze and, of all things, at the moment of greatest proximity, they are no longer there for him, in his consciousness.]

[5] Sie aber, schöner als jemals, streckten und drehten sich, liessßen das schaurige Haar offen im Wind wehn, spannten die Krallen frei auf den Felsen, sie wollten nicht mehr verführen, nur noch den Abglanz vom grossßen Augenpaar des Odysseus wollten sie solange als möglich erhaschen.

Hätten die Sirenen Bewußsstsein, sie wären damals vernichtet worden, so aber blieben sie, nur Odysseus ist ihnen entgangen.

But they, more beautiful than ever, stretched and turned, let their eerie hair blow open in the wind, stretched their claws freely on the rocks, they no longer wanted to seduce, they only wanted to catch the radiance of Odysseus' great pair of eyes as long as possible.

If the Sirens had been conscious, they would have been destroyed then, but so they remained, only Odysseus escaped them.

[The Sirens, too, are now transformed. Since it is no longer a matter of battle and victory for them, they are now free to be what they are. Thus, even with their eerie hair and claws, they are now more beautiful than ever. If, however, they had realised that Odysseus had defeated them, they would have been destroyed. As it is actually said in later Greek tradition, after Odysseus had continued his journey, they threw themselves into the sea and died. This is similar to Kafka's Bridge, where the bridge is destroyed when it wants to know what is happening on it].

[6] Es wird übrigens noch ein Anhang hiezu überliefert. Odysseus, sagt man, war so listenreich, war ein solcher Fuchs, dassß selbst die Schicksalsgöttin nicht in sein Innerstes dringen konnte, vielleicht hat er, obwohl das mit Menschenverstand nicht mehr zu begreifen ist, wirklich gemerkt, dassß die Sirenen schwiegen und hat ihnen und den Göttern den obigen Scheinvorgang nur gewissermaßen als Schild entgegengehalten.

Incidentally, an appendix to this has been handed down. Odysseus, they say, was so cunning, such a fox, that even the goddess of fate could not penetrate his innermost being; perhaps he really did notice, although this is no longer comprehensible with human understanding, that the Sirens were silent and only held up the above apparent action to them and the gods as a shield, so to speak.

[It is not easy to see what Kafka is trying to say in this appendix. It seems that he is hinting here at the possibility that a human being can harmoniously unite in himself the two contradictory possibilities presented in the narrative. The first is the Odysseus of the classical tradition, the cunning one who knows his way around, calculates, considers and acts consciously. The other possibility becomes visible in Kafka's new figure of Odysseus, which he contrasts with the classical one: a man who rests in himself, trusts completely in his inner strength and can shut out everything around him from his consciousness. The "apparent action" then consists of him behaving like a child who is completely absorbed in the world of his play, while he does this quite consciously in order to protect himself.

Thinking of the difference Kafka formulated between the "world in his head" and his "dreamlike inner life", one could perhaps say that Odysseus' behavior may not be comprehensible by human reason, but that the possibilities of being human suggested by Kafka here may become visible in the world of inner dreams.]