Data on Religion in Japan

A number of comprehensive surveys on religion in Japan have appeared in recent decades, providing a detailed and up-to-date picture. Most important are a publication on the ISSP survey by the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK, 2019), a Study of the Japanese National Character by the Institute of Statistical Mathematics (ISM, 2017) and a publication by the ministry in charge (MEXT, 2015). Some of the most interesting results will be summarised here.

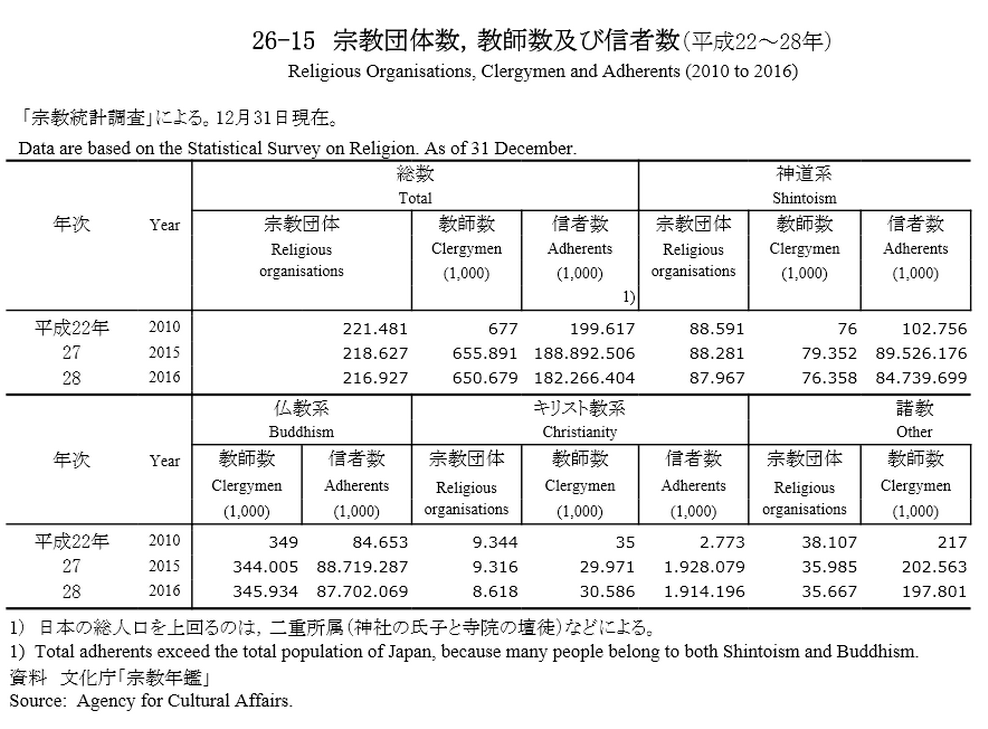

As they have done for decades, the Agency for Cultural Affairs continues to publish an annual bilingual summary of its surveys, even though their problematic nature has been known for a long time:

The statistics on the number of believers are practically worthless. This applies above all to the data on Shintoism, which can only be a few percent of the population, as surveys show (see below).

The number of buildings of the individual organisations, on the other hand, should be largely correct. This at least gives an indication of how present the individual religions are in Japan. However, one cannot compare an abandoned Shintō shrine somewhere in the forest with the imposing main temple of a New Religion, which is visited by millions every year.

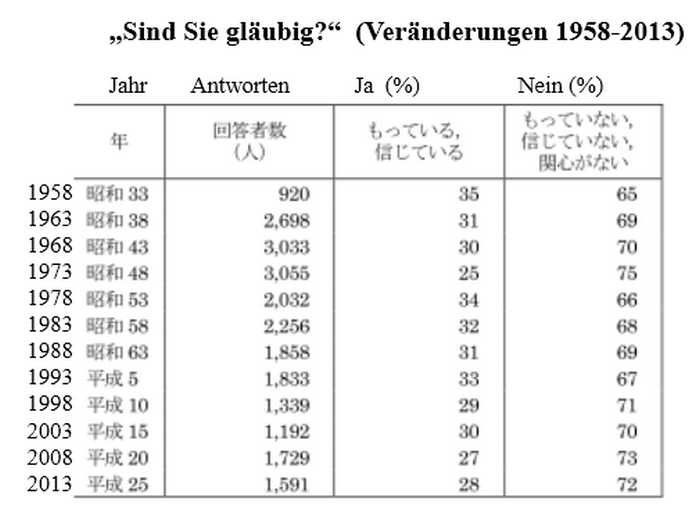

That the explanation above in Note 1) does not apply has been shown for decades by numerous surveys like this one:

"Do you have any personal religious faith?" (changes 1958-2013)Year Answers Yes (%) No (%)

According to this, the number of people in Japan who describe themselves as believers has been hovering around 30% for six decades (see also Q1 below). This is also confirmed by other surveys, such as that of the Yomiuri Shimbun or the large ISSP survey (No. 29; cf. No. 14). It should be noted, however, that the differences between the age groups are often very large, between those in their twenties and those in their sixties or seventies often three times the percentage and in some cases more than ten times. This is the case, for example, with ISSP question No. 29. (Among those who pray daily at the home altar, the percentage is even more than 20 times higher among the oldest compared to the youngest in 1998!) The differences between the sexes are less significant, with women usually (not unexpectedly) showing a somewhat more positive attitude towards religion. In all the details, the differences between the various population groups can be made visible in the interactive table of the ISM (click the link there!).

The MEXT figures are also corrected by surveys where belonging to a particular religion plays a role. This is particularly true for the Shintō. In the most recent ISSP surveys (2008 and 2018), Buddhism is clearly the dominant religion in Japan, as in all previous surveys, with 33% and 31% respectively (see also ISSP 18-20). The Shintō does not even reach a tenth of this with 3.1% and 2.5% respectively and also a declining trend. Christianity and other religions come to only 0.7/1.2% and 0.8/0.5%.

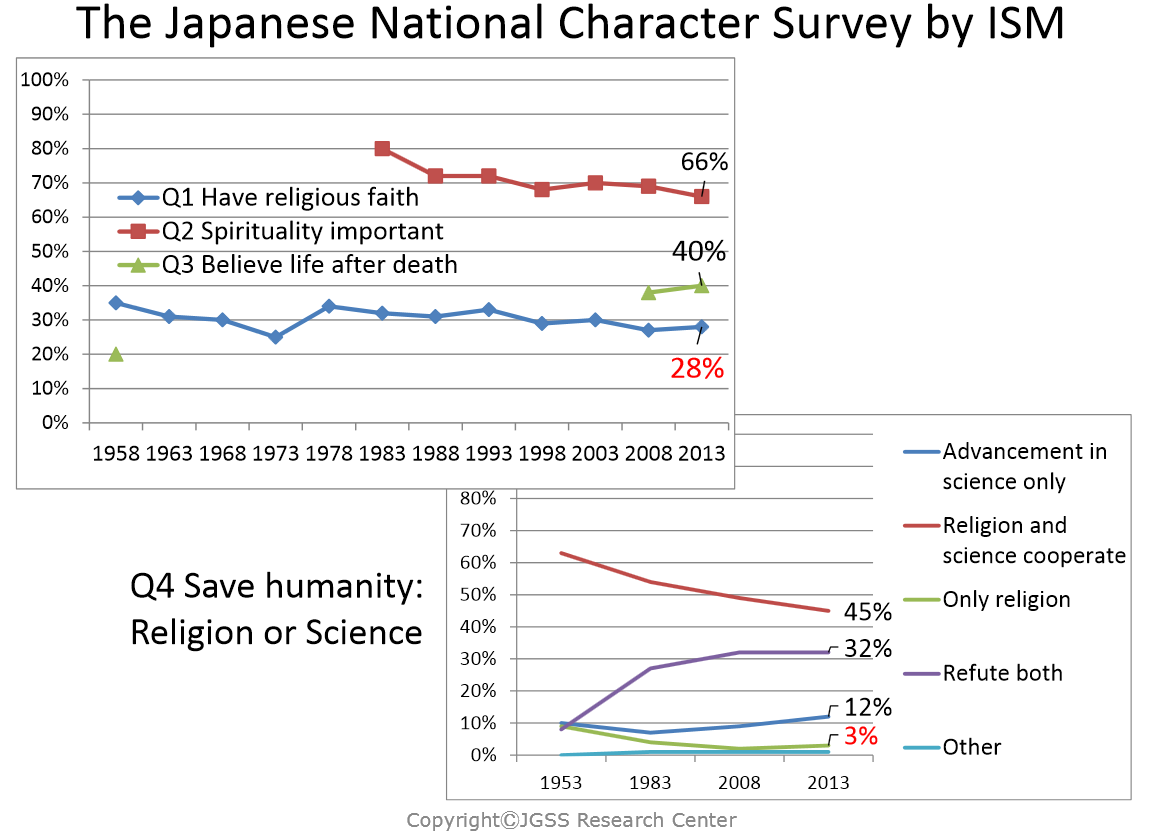

On this chart the survey results of the ISM are clearly presented. It is remarkable that the percentage of believers (Q1) is more than doubled by those who consider a religious attitude important (Q2). Belief in an afterlife (Q3) is 40% (cf. ISSP 15). On the other hand, there are only 3% who believe that only religion can save humanity (Q4, cf. ISSP 9a).

The basic tendencies that are indicated here become visible in great detail and differentiation in the tables of the ISSP. It is worth browsing through them to get a better sense of the relationship of people in Japan to religion. If one tries to order the complex results (admittedly somewhat roughly), one can perhaps summarise the positive responses in relation to religion into three groups of percentages as follows:

The percentage of believers (the blue line above, Q1) forms a middle line with a slight downward trend at around 30%. Around 30% are also religious activities and attitudes that do not require any particular commitment, such as praying fairly regularly (ISSP 24), interest in Zen or similar practices (ISSP 39), praying at least occasionally in front of a home altar (ISSP 36/37), as well as the belief in finding comfort through religion in difficult times (ISSP 31B) or the conviction of the benefits of religion for human relations, ethical awareness and helping the poor (ISSP 44). Also the ideas of heaven and hell, of the supernatural powers of the ancestors, etc. (ISSP 15) fall into this percentage range.

The relationship to religion, especially in Japan, is often co-determined by family and other traditions. However, when it comes to religious belief as a personal conviction that essentially determines one's own life and forms its basis, the percentages often fall to only a few percent, such as the 3% above (Q4). For example, only 6.5% believe that one's life has meaning only with God (ISSP 16C). Only 10% have read a scripture at least once a year. A full 5.2% attend religious services somewhat regularly (ISSP Z.23) and 3.1% additionally attend religious activities (ISSP 25). Only 3% are sure that God really exists (ISS 13.6).

In contrast, we have significantly higher percentages in the third group above the blue line, where it is about religion in the broadest sense and often rather vague and undefined feelings about religious phenomena. It turns out that two-thirds or more of people in Japan are at least not hostile to religion. More than twice as high as the number of believers is the number of those who feel a special closeness to the individual religions in Japan. For the years 1998/2008/2018, the figures are 49/66/62% for Buddhism and 15/21/21% for the Shintō, with a clear upward trend. Also because of the possibility of multiple answers, Christianity even receives 11/12/12%.

62% of people in Japan have at least the vague feeling that there is God or a higher power (ISSP 13). The same percentage believes that if a person does something bad, it will not go unpunished (ISSP 38C). Prayers in times of need are known by 59% (ISSP 41). The number of those who have ever received amulets or talismans (82%) or bought a horoscope (75%) is even higher, and the traditional shrine/temple visits at New Year and cemetery visits on certain Buddhist holidays even come to 90% and 93% respectively (ISSP 43, cf. Yomiuri).

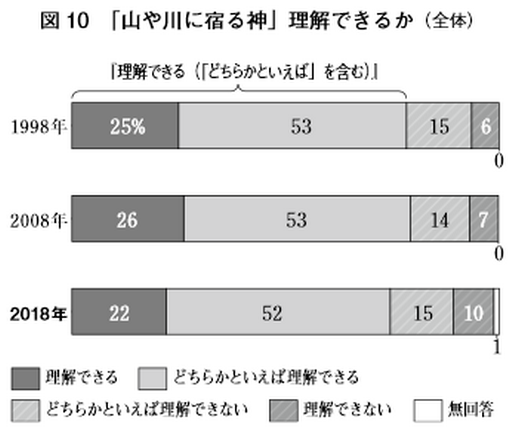

That some traditional religiosity, often perhaps subliminally, still lives on in Japan today can be seen from the high rate of agreement (74%) to the following question (ISSP 40):

Can you imagine that gods live in mountains and rivers (= in nature)?

(from left to right: yes, rather yes, rather no, no, no answer).

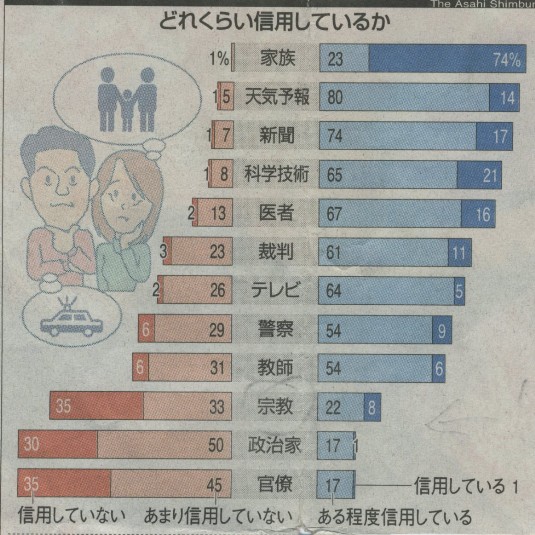

This contrasts with the distrust of religious organisations in Japan, which is particularly high after the terrorist attacks by the Aum sect in 1995 (see also ISSP No. 7):

Degree of trust in:

Family

Weather forecast

Newspapers

Science

Doctors

Courts

Television

Police

Teachers

Religion

Politicians

Civil servants (bureaucrats)

do not trust/trust little//somewhat trust/trust

[Asahi Shimbun, 21. 3. 2008]

[image:image-1]

[JGSS Research Center, Osaka University of Commerce, 2017]

(The evaluations of the other organisations are also interesting for understanding the social situation in Japan).