[Choose map by clicking it, enlarge by Mouse Over or clicking.]

Japan and Exoticism: Introduction

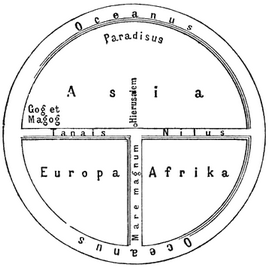

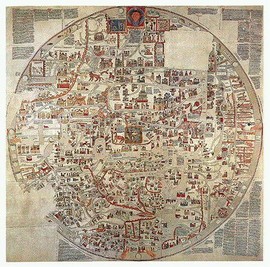

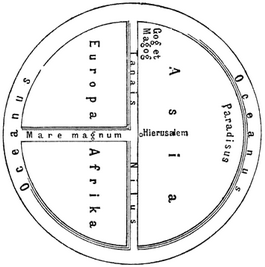

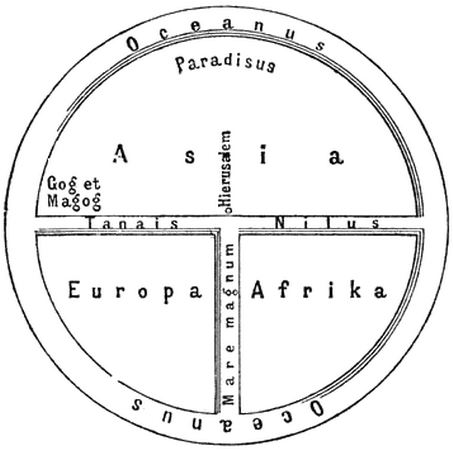

Japan first appeared on European maps at the beginning of the modern era under the name Zipangu. There is, however, a prehistory in which dream and reality mix, as so often later in the history of relations between Europe and Japan (see Kapitza). Medieval maps showed the earth as a disc surrounded by an ocean, with the continents of Europe, Asia and Africa, not including America, of course. The map above on the left shows this scheme in its simplest form, with the East at the top (on the right, for comparison, the same map is arranged north to south). So Europe is at the bottom left, Africa on the right and Asia at the top. For the biblical orientation of the map it is important that Jerusalem is exactly in the middle and, more importantly for our context, that Paradise is at the top in the East. The map in the centre (Mappa Mundi Hereford, 13th century) is very confusing because of the many details. At the very top you can see [especially when enlarged: move the mouse over the map] that Paradise is shown as an island east of the Asian mainland. When Marco Polo reported that the Chinese knew of an island kingdom of Zipangu in the East, with great riches, especially gold, the dreams of many Europeans of paradise and immeasurable treasures were increasingly directed towards this legendary island of Zipangu. For Columbus, this was an important motivation for his daring voyage across the Atlantic, along with the hope of finding a sea route to India. The importance of this is reflected in his journals, where he searches feverishly for the island of Zipangu on his arrival in Central America, and is even prepared to accept similar-sounding names, even Cuba, as the destination of his longing.

It is interesting to note that, while the idea of Japan as a dream island persisted, mostly subliminally, over the next few centuries, the first Europeans to visit the country, and in some cases to get to know it through extended stays, generally reported on it in a matter-of-fact and balanced way. This applies not only to merchants and travellers, but also to many missionaries who lived in the country from the 16th century onwards, despite some prejudices about religion in Japan.

This attitude was particularly pronounced during the Enlightenment, as the following quotation shows:

But the greatest aspiration of man is the knowledge of himself, and this we owe largely to travellers. We are brought up in a country among citizens who all have the same faith, the same customs, and generally the same opinions: these gradually weave themselves into our senses and become a false conviction. Nothing is more capable of dissipating these prejudices than the knowledge of many peoples, among whom customs, laws, and opinions are different; a difference which teaches us, with a little effort, to discard that in which men disagree, and to take for the voice of nature that in which all peoples agree. (Albrecht von Haller).

This attitude is especially true of the scholars who were called to Japan after the opening of the country at the end of the 19th century and who gave Europeans a complex and mostly balanced picture of Japan. It is all the more surprising, then, that around the same time a movement began that created a very different image of Japan, one that was more reminiscent of the dream island of Zipangu than of the real Japan that many people had come to know so well by then. This was a new cultural movement in Europe, exoticism, which used Japan as a projection screen for its own dreams and aspirations.

The roots of exoticism lie in a feeling of insecurity or even fear in the face of the advancing mechanisation and rationalisation of modern life, a feeling that is already evident in painting, for example in Breughel's Tower of Babel, as a reference to the limits of human endeavour. Then, in Romanticism, it becomes noticeable as an attempt to return to the past, especially to the Middle Ages. Ultimately, however, dreams increasingly focus on distant, exotic countries.

From around the middle of the nineteenth century, a growing number of artists and intellectuals turned away from European culture, or at least viewed it more and more critically, and created imaginary, exotic counter-worlds from real or only imagined elements of foreign cultures, onto which they projected their own desires and dreams. After Tahiti, India and China, in the second half of the 19th century the focus shifted increasingly to Japan. Important occasions for this were the International Exhibitions of 1862 in London and 1867 in Paris, and the wave of Japonism that they triggered. (The latter must be distinguished from exoticism, despite some similarities).

The German poet Max Dauthendey provides a good example of how 'home-grown' exoticist dreams differ from the reality of the country in question. For him, Japan was the land of his longings and dreams, but when he finally got there, he wrote to his wife: "If I did not have Japan in my memory, as it always seemed so beautiful to me from afar at home, I could almost call it boring and sad now". (1906) It is almost touching that he had to admit that the country of his dreams was only a figment of his imagination. But then as now, he could have discovered many beautiful and wonderful things in Japan, even mysterious and fantastic things, if he had paid a little more attention to the real Japan, as many of his compatriots did at the time.

If exoticism were merely a curiosity of cultural history, there would be no need to study it today. Unfortunately, however, its influence can still be felt in many false and imaginary ideas about Japan that are disseminated in the media, literature and art. In fact, the influence of exoticism even extends to the images and ideas that the Japanese themselves have of their own culture.

Indeed, parallel to the exoticist tendencies in Europe, many Japanese began to grapple with questions of their own identity in their confrontation with Western cultures. This discussion reached a climax in the late 1960s with the appearance of numerous publications, most of which are summarised under the term "Nihonjinron". What is surprising is that many ideas and stereotypes of European exoticism appear in these "discourses on the Japanese", even those that have nothing to do with Japanese reality. In other words, the Japanese partly determine their own culture and society through ideas that were designed or dreamed up by Europeans as a counter-image to European culture.

It seems that European longings and Japanese interests - from the emotional and ideological to the concrete economic and political - confirm and reinforce each other in such a way that it becomes difficult to critically refer back to actual realities. This explains some extreme tendencies and positions in the "Nihonjinron" and the uncritical way in which they are still often adopted outside Japan.