Kafka: Introduction

"From the point of view of literature, my fate is very simple. The desire to portray my dreamlike inner life has relegated everything else to the sidelines, withering in a terrible way and it will not stop withering. Nothing else can ever satisfy me."

(Diaries 6. 8. 1914)

"The enormous world I have in my head. But how to free myself and free it without being torn apart. And a thousand times rather be torn apart than hold it back or bury it in me. That is what I am here for, that is quite clear to me."

(Diaries 21. 6. 1913)

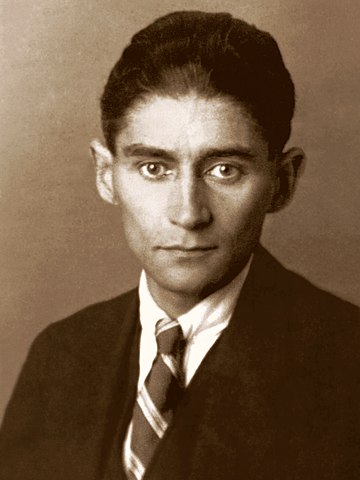

When Franz Kafka died in 1924 at the age of 40, a year after the above photograph was taken, few knew or appreciated him. Today, 100 years later, people all over the world are fascinated by his works and the literature about him is incalculable. Kafka's willingness to sacrifice everything else in order to give expression in his literature to the "enormous world" and the "dreamlike life" he felt inside him still impresses people to this day. But access to his works remains difficult. Kafka created a whole new kind of literature to free himself from the constraints and prejudices of traditional language. Only gradually is it dawning on many that what he describes is not a grotesque, absurd, or "Kafkaesque" world, but that he makes visible an inner truth that is obscured by our bias in conventional thinking. (more details)

I remember my first Kafka reading when I was still at school. I couldn't get anything out of The Metamorphosis. Up in the Gallery was explained to us by a young trainee teacher. The look on our uncomprehending faces must have irritated him so much that he shouted at us: "Don't you understand? Don't you understand?" Today, both texts are among my favourite readings, in which I keep making new fascinating discoveries.

How was that possible? I see two main reasons. One are the, unfortunately few, good publications on Kafka - not those about Kafka's personality and his circumstances of life, which are usually not very helpful or even misleading, but those that focus on what alone was important to Kafka, his texts. The other reason is a fact, which I only gradually became aware of, namely that one's understanding of Kafka's texts grows with one's own life experiences. However, I had not expected that my move to a university in Japan and the decades of new experiences there would mean such a leap in this direction. How is that possible? Kafka knew hardly anything about Japan and very little about China. How was he able nevertheless to describe in his texts phenomena that are very much alive in the Japanese language and culture, but largely unknown and misunderstood in Europe? But isn't that precisely what art and the artist are about, the ability to make visible deep, inner, universal truths that are often completely absent in the traditional conceptual world, its language, its concepts and forms of expression?

That this also required a different attitude, a different approach to reality, is hinted at by Kafka in the above quotations. While he first speaks of the "enormous world" in his head that threatens to tear him apart, only a year later he is concerned about his "dreamlike inner life". What this difference means to him is shown by Kafka especially in Up in the Gallery.

I would also like to add a quote from his girlfriend Milena Jesenská, who probably understood him better than any other person in his life.

Certainly the thing is that we are all apparently able to live because at one time or another we have fled to a lie.... But he has never fled to a protective asylum, to any. He is absolutely incapable of lying, just as he is incapable of getting drunk. He is without the slightest refuge, without shelter. That is why he is exposed to everything we are protected from. ... This is not a man who constructs his asceticism as a means to an end, this is a man who is forced into asceticism by his terrible clairvoyance, purity and inability to compromise.[Milena Jesenská to Max Brod, early August 1920]

This unconditional striving for truth occasionally even takes on almost religious traits in Kafka, when at the height of his creative work (in Zürau) he speaks of only being able to find happiness "if I can lift the world into the pure, the true, the unchangeable". (Diaries, 25. 9. 1917) Something of this, I think, is felt by every reader in Kafka's texts, and this fascination leads one to deal with him again and again. And how much it is worthwhile to dream with Kafka, to discover the "dreamlike inner world" in his texts, is something which, as for me, I have often experienced and would now like to try to convey here.

Since time immemorial, human dreams have found expression in myths and legends. Kafka ties in with this when he takes up such motifs in some of his short stories. His Prometheus is particularly interesting here, especially because of the contrast with Goethe's poem of the same name. In Kafka, the whole development towards European modernity is, as it were, reversed to its pre-mythical "substratum of truth".

Another hero of Greek mythology, Ulysses, is at first almost ridiculed in The Silence of the Sirens for his "many devices", but then reveals himself to be probably the most positive figure in Kafka's writings, revealing an almost utopian alternative possibility of human existence.

Particularly important for understanding Kafka's world is his short, very dense text Up in the Gallery, for which I have therefore written a separate introduction. Also introduced separately is a theme that, in addition to some biographical testimonies, plays a central role above all in The Metamorphosis and Kafka's last work Josefine, the Singer or The Mouse Folk. It is about a special form of emotional dependence. Even today, this is hardly present in the world of German language and culture, but Kafka nevertheless recognised and comprehensively described it as an important element in human relationships. It is explored here by way of the Japanese language and culture, where it is known as amae.

Finally, a particularly original formulation of Kafka's "world in the head" and his "dreamlike inner life" can be found in "The Bridge", a playing with the limits and possibilities of being human.