Encounters in Japan

Arrival in Japan

Japan! At last! Only a few shadowy outlines of the coast could be made out, but it had to be Japan. Or just some islands off the coast? He smiled involuntarily. After all, Japan consisted only of islands. That's why you could only get there by ship, at least in the past. And for a moment, he felt like one of those early travellers to Japan who, after a long, arduous and dangerous journey, finally saw the coast of Japan in front of them and raved about the rocky coastline, then covered more with pine trees. This was the way to travel if you really wanted to experience Japan! Even if the journey from Nakhodka in Russia, which took less than two days, did not quite compare with the many experiences and impressions of a trip halfway around the world as in the past. On the other hand, a sober merchant (but Troy enthusiast) like Schliemann (and this is how we know him from schoolbooks) could use the long voyage to improve his knowledge of French and then apply it by writing his report on Japan in French. With such thoughts running through his mind, the ship sailed into Tokyo Bay and past the endless port facilities to the dock at Yokohama.

The immigration formalities had apparently gone smoothly, and the first thing he remembered afterwards was finally standing on the train he had been told would take him to his accommodation. It must have been rush hour, and the train was crowded, mostly with men returning from work. His first impression of the people of Tokyo remained unforgettable: he looked over their black-haired heads, beneath their white shirts and black trousers, almost uniform. And the faces all seemed the same to him. Would he ever learn to tell them apart, to see the individuality in them? It would be a few years before he did, but then he would be astonishingly successful.

His thoughts returned to his first evening in Japan, when he had an encounter (at the YMCA) that prepared him to get to know not only the country and its people, which were still so foreign to him, but also many special people from other countries, from rather quirky eccentrics to impressive personalities, whom this country had attracted and shaped.

As he stood at the reception desk, an elderly man approached him and very kindly asked if he would be interested in sharing a double room with him. It would be much cheaper and he was a quiet sleeper. It was hard to refuse a request made in such a sympathetic and unassuming manner, and so over the next few days the opportunity arose for long and very interesting conversations, especially about the man's eventful life. He had left his home in Austria at the age of sixteen to see the world. After many adventures, he ended up in South America, where he worked so hard for almost 30 years that by the time he was 48, he owned an apartment building and lived in modest comfort. Now he could fulfil his great dream of travelling the world and pursuing his hobbies as he pleased. He had spent his first years in the South Seas, where he had collected many rare shells. By now the collection had become so large and exquisite that it attracted worldwide attention. Even the Japanese emperor, he revealed with a shy smile, had invited him to show him his collection. But modest as he was, he had not dared to accept the invitation. He had no idea what an honour it was in Japan to be invited by the emperor. And he was even less aware that in private the emperor was a friendly, modest marine scientist, not so different from himself, and that he would certainly have enjoyed talking to him. Emperors have dreams too...

Tanabata

What had brought him to this point? The Japanese summer was almost unbearably hot and humid for Europeans, he knew. But here on the train it was just terrible. It was so crowded you could hardly move. There was air conditioning on the express train to Kyoto the other day, but here on the route to northern Japan they used the old trains with ceiling fans, which were practically useless in this situation. Drenched in sweat, he stood between all these people, looking over their black-haired heads. His height at least gave him a bit more air and a better view up there. But down below it was all the more cramped. He had just managed to squeeze his suitcase between the people and put his right foot on the floor next to it, but there was no room for his left. Only the tip of his foot touched the ground between all the other feet. At least, he thought with a touch of gallows humour, I now understand almost physically what it means not to have a foot on the ground. Sometimes he felt strange in this environment. The journey through Tokyo and the search for the right train had made him painfully aware of his lack of Japanese. But the friendly glances and helpfulness everywhere made him forget that quickly. And the forced physical closeness on this train prevented him from feeling lost, even though the situation became more and more unbearable as time went on.

Should he have given up this journey? But no, he was young and adventurous, and he perked up a little at the thought of his destination. He had long dreamed of visiting the famous Tanabata festival in Sendai, with its wonderful decorations made of paper, artistically folded in all colours and shapes. This festival was celebrated there in two days (according to the lunar calendar, originally in autumn on the 7th day of the 7th month) in memory of the Celestial Princess who, separated from her beloved husband by the Milky Way, was only allowed to meet him once a year, on this day. The fact that the festival now took place at the hottest time of summer was due to the change to the European calendar.

While he was daydreaming about this romantic old story, the train was about halfway through its four-hour journey, and by the time it stopped again at a station, he was too tired and exhausted to bother to find out the name. But then he was suddenly wide awake. A seat had opened up right next to him. Instinctively, he wanted to jump on it. Then he noticed an old gentleman standing next to him, who of course had the same aim. For a moment they looked into each other's eyes. The old man was visibly exhausted, and the hope of finally being able to sit down was reflected in his eyes. At the same time something almost unbelievable was clearly visible, namely that he would have to give up this seat because he naturally wanted to offer it to the foreign guest. Or was it simply a reserved modesty and kindness that he would show to anyone? In any case, the person addressed was so overwhelmed that he forgot everything around him and only later remembered that his face must have reflected a similar feeling to that of the old gentleman, namely the hope of finally getting a seat and at the same time the willingness to let the older man go first.

While all this was going through his mind, hardly a second had passed. The next thing he remembered was something quite wonderful. Suddenly, they were both sitting side by side on a small bench with room for two. Again, they looked into each other's eyes for a moment, and the happiness of that moment, which they shared and which was reflected in their faces, was like a glimpse of paradise, a paradise where people, despite all their differences, simply understand each other as human beings and live together in harmony. Good thing I don't speak Japanese, he thought. Otherwise, I would probably have dropped some stupid phrase that would have destroyed the whole magic of this moment. What could they have said to each other beyond what they had read in each other's eyes?

Happiness in the country

He had been his guest in Germany during a youth exchange, and now he was inviting him back to his home in Japan, and the special thing about it was that it was an invitation to a large farm north of Tokyo. It was like being in another world. Three generations lived under one huge roof according to rules that seemed to be centuries old. It was summer and very hot. When he got up in the morning and was asked to come to the breakfast table, the whole family was already busy in the house and in the fields. The sister sat down with him to try out her English. Later the grandfather joined them. It turned out that he had already finished work. Like most of the rest of the family, he had started work in the middle of the night, as it was almost impossible to work in the fields during the day in the heat. Now he was sitting here, smiling happily, enjoying the end of his work. He had brought a bottle of rice wine, and they drank a glass together. From the start, the grandfather refrained from using language when he realised that his guest's Japanese was not good enough. Using gestures and lively facial expressions, and smiling all the time, he managed to make them understand each other in a way, and splendidly, much better than through his granddaughter's bumbling English. They wanted to communicate because they liked each other, and somehow it worked. So he understood that the old gentleman, out of consideration for his guest, drank from the small rice wine bowls that were customary on such occasions, but otherwise from a larger beer glass, and that, he implied, was why he was always so happy, though his laughter left it open how serious he was. All he could remember of the rest of the conversation was that they had joked and laughed a lot in good spirits. He would never forget the old man's happy smile. In the days that followed, he often met him in the village, in the fields, in the house, almost like a good guardian angel, and always that smiling face! Even later, when he thought of him, he always saw that face and thought that the old man must have been the happiest man in the world.

As he reminisced, he felt that he was perhaps overdoing it. But aren't there such experiences and encounters in everyone's life, especially when they are completely new? Had not, in 1860, Count zu Eulenburg said enthusiastically about Japan: "If one could live here in the countryside, among these good people and in this delicious nature, one could be truly happy..."? And had not even Kafka, during his first weeks in the country with his sister Ottla in Zürau, spoken in unusually positive terms about his encounter with a farmer? While Kafka, in his diary entry, initially tries to suppress his enthusiasm with irony, what follows is a litany of praise that is almost unbelievably far removed from everything else that Kafka himself and his protagonists experience.

Peasant K. (powerful, superior narration of the world history of his economy, but friendly and good). General impression of the peasants: nobles who have saved themselves in agriculture, where they have organised their work so wisely and humbly that it fits seamlessly into the whole, and they are protected from any vacillation and seasickness until their blissful death. True citizens of the earth.

[F. Kafka, Diaries, 8 October 1917].

Why do Japanese people all look the same?

It is often said of the Japanese, as of the Chinese and some other peoples, that they all look alike. In fact, he remembered how much it had irritated him when he first came to Japan that he could not even remember the faces of his friends and relatives, and that the faces of the people around him seemed so expressionless or even mask-like. But then the time came when, to his great delight, he suddenly discovered more and more familiar faces around him. He even found some of his relatives and friends in Europe and was amazed at the similarity between physiognomy and personality. This became particularly clear when he met his wife's youngest uncle for the first time, who immediately reminded him of his youngest uncle in Germany. It was the same cheerful and friendly manner which, surprisingly, he immediately thought he saw in his face, and which he then found confirmed. So it was possible to read a Japanese face if, as he now realised, one forgot the features that were striking to a European but not to a Japanese. The more one learnt to ignore the features that most Japanese had in common, and instead to pay attention to those that expressed individual personality, the more one recognised the Japanese in their individuality, and so they remained in one's memory.

That, in this way, the physical characteristics of the Japanese, which some like to associate with ideas of race, also fade from consciousness was made clear to him by an experience a few years later. A new colleague from America had arrived at the international university where he worked. By chance he met him on campus and they had a long and interesting conversation. When he told another colleague about this and the colleague asked him if the new colleague was of Japanese origin, he was suddenly very confused. He tried to imagine what the colleague looked like, Japanese or Caucasian, but he couldn't, even though the differences were clear and he had got a good impression of him and would certainly recognise him. For a moment he was embarrassed, but then a feeling of happiness came over him. So he had learned not to be consciously aware of ethnic differences, and instead to pay attention to the individual characteristics in which a person's personality is expressed! If only we could do that all the time. That would be the end of racism!

Mount Fuji

Almost every early account of Japan contains a description of Mount Fuji. Occasionally it is rather sober and objective, but more often it is deeply impressed and enthusiastic, to the point of exotic rapture. The whole range of reactions to Japan can be seen here, often right up to the present day. Today it is almost impossible to think of Japan, even if you know little about the country, without immediately seeing Mount Fuji in your mind's eye. Unlike many other images of Japan, which often bear little resemblance to reality, this volcanic mountain does exist, and few would doubt that it is extraordinarily impressive. He has been fascinated by Mount Fuji ever since he moved to Japan, especially as he is lucky enough to be able to see it from his dining room window when the weather is good, and almost every day in winter. Mount Fuji is particularly impressive in the morning, when the snow-white mountain is illuminated by the first rays of the sun, and even more so in the evening, when the sun sets directly behind it and the silhouette of the mountain becomes increasingly visible against the red of the evening sky.

When he moved into the house years ago, the view of Mount Fuji was framed on either side by two pine trees which, in a rare natural phenomenon, parted at the height of Mount Fuji - in Japan a particularly auspicious sign of long life (pine) and happy togetherness. A Japanese painter might add a crane (long life) to complete the lucky picture. But that would take us away from reality, which in Tokyo includes the fact that the two pine trees have now fallen victim to pollution, and that instead of cranes it is crows living on garbage that fly past Mount Fuji. None of this detracts from the majesty of Mount Fuji. It is most impressive when seen from one of the surrounding mountains. The Fuji then appears so high that he could not even find it the first time and thought it was behind the clouds, until he discovered the peak high above those very clouds. But what he found truly overwhelming was the view from Otome Pass near Hakone. If you approach the top of the pass from the side facing away from Mount Fuji, the mountain only becomes visible for the last few metres and then rises higher with every metre you get closer to the top of the pass, until finally, from this proximity and height, you can see it in all its almost unbelievable size, not to mention its ever-impressive beauty.

Rural Tokyo

Once again, he had bought the Christmas tree for his family very early in the year, as it was impossible to completely escape the trend in Japan of celebrating "Christmas parties" with students, friends and acquaintances weeks before Christmas. This left little room for the "real" Christmas he knew from Germany. At first, the university even took down the big Christmas tree at the entrance to the campus on Christmas Day, until he protested.

But that's not what this is about, it's about how he bought the tree from a farmer nearby. It sounds like they live in the country, but his town is about halfway between the centre and the outskirts of the metropolis of Tokyo, of which it is a part. It is mostly densely built up, but like other parts of Tokyo, there is still farmland and even a vineyard near the station. In many parts of the town, away from the main thoroughfares, there is an almost village-like atmosphere, and even small patches of woodland can be found here and there. He remembered how he had once gone for an evening walk in such a small wood, how he had thought of German forests and dreamed of Grimm's fairy tales. And there, in the middle of Tokyo, he actually met an old woman who had collected "brushwood" in the forest and carried it in a bundle on her back, just like in Grimm's tale!

He found his Christmas tree farmer by chance, thanks to a tip from a friend. Turning off the main road into a small lane, he suddenly found himself in another world. Behind a modest farmhouse, a vast open space opened up, sparsely overgrown, while around it, multi-storey houses stood close together, an indication of the high local land prices. This farmer must be a multi-millionaire! But he didn't look like one. First he calmly finished his furrow, then he came over to the visitor. They talked about everything: the weather, the soil, farming. In between, the farmer dug up a large turnip, which he recommended as particularly tasty, cut a cabbage for the visitor, helped him choose the large fir tree, which he left at a very modest price, and even offered to deliver it to the house. The woman joined them, they chatted, he bought some more vegetables, but money did not seem to interest the couple. When asked how such a large plot of land could be kept in Tokyo, he pointed to the densely packed houses at the end of the plot. The elderly man had had to sell a third of his land there when his parents died to pay the inheritance tax. A farmer in Tokyo could probably not last more than three generations. . .

And indeed, when he went to buy another Christmas tree a few years later (the old one had survived so long in the garden but had grown too big), he immediately noticed the change. The son greeted him and, noticing his questioning look, said: "You can see for yourself. When my father died, we had to sell almost half the land to pay the inheritance tax. We are the last farmers here."

But Tokyo still retains much of its village atmosphere. Those who only know the city as loud and big, as a mass of concrete and people, may wonder how the people of Tokyo can stand it. But there is also the "village" Tokyo, with its old structures that have grown over time. Here the temples and shrines with their old trees, often even larger parks and their countless traditional festivals serve as a bulwark, in which the sense of community lives on. And, of course, the many small shops, craft workshops and pubs with their village traditions. Where large-scale projects have not radically changed the urban landscape, as in the city centre, such oases of tranquil life can still be found.

Towards the end of his stay in Japan, he lived for a few months in such a neighbourhood, close to the centre, where the old structures are still clearly visible - and immediately felt at home. Yes, he often thinks of Tokyo with a sense of home, and it is places like this that he remembers most fondly. It didn't take long for him to feel that people knew him in his new surroundings. On his daily walk to the train station, he encountered many friendly faces, and was greeted even in shops he had only visited once. Maybe they had talked about him, the (hopefully nice) strikingly tall blond new man in the neighbourhood. A special 'friendship' developed with an older gentleman with whom he had never spoken for more than a brief greeting. Nevertheless, he looked forward to meeting him every time he went to the station, and the feeling was obviously mutual. When he passed his house in the morning, the old man had apparently been up for a long time, had placed his considerable number of bonsai plants outside the door and was now busy with them. When he met him for the first time, the old man seemed so content and happy, and then looked up at the passer-by with a smile, that he could only smile back and give him a quick greeting. This is how the 'friendship' was born, consisting of nothing more than a daily greeting, but obviously making the day a little nicer for both of them. Not wanting to disappoint the old man by staying away, he also made sure to say goodbye before he went back to Germany. The bonsai were obviously a way for the old man to keep a bit of the country life in and with nature. Many similar hobbies are very popular in Tokyo and elsewhere in Japan, with some plant growers achieving incredible perfection and artistic mastery.

This was demonstrated to him once when he took advantage of the fine autumn weather to visit the botanical garden close to the nearby temple, where a large chrysanthemum exhibition was held every year at this time. There were prizes for the most beautiful specimens, awarded by local personalities, mayors and even the Governor of Tokyo. The ambition of the many growers was obviously great, and it was fascinating to see the variety of shapes and colours that could be created from one flower. Particularly impressive, of course, were the often huge clusters grown from a single stem, the tall triple-stemmed chrysanthemums with single very large flowers in many striking shades, some with simple full flowers, others with refined petal shapes. What impressed him most, however, were the bonsai arrangements in which the chrysanthemums, often together with small stones and similar materials, were shaped into traditional motifs and small landscapes. With each piece you could feel the perseverance and dedication with which the growers had worked on it over many years.

Tokyo

He had lived in Tokyo for over thirty years, but it was only when he was trying to answer questions from a friend in Germany that he first realised how difficult it is, at least from a German point of view, to understand what "in Tokyo" actually means. Strictly speaking, he could not say that he lived in the city of Tokyo, because it no longer existed in the administrative sense since 1943. It would be correct to use "in Tokyo" in the sense of "in the Tokyo prefecture", but that is not really what is meant by "living in Tokyo". Someone who lives in the mountains that belong to Tokyo, or on one of Tokyo's Pacific islands, can also say that. In the past, the 23 wards (ku) were considered to be the actual city of Tokyo, but since these have been upgraded to cities in English, there is now only a conglomerate of cities. So where is the capital of Japan? It is not possible to define it precisely. Strictly speaking, it is the entire prefecture, which is why it is called to (capital). However, you would not expect someone to call from one of the Pacific islands and say: "I'm in Tokyo now". It might all seem very confusing, but he hadn't met any Japanese who had thought about it, and he hadn't either. Even the UN generously overlooks the administrative fragmentation of Greater Tokyo into eight prefectures and countless small towns, and lists it as the largest metropolitan area in the world, with more than 35 million inhabitants. How fortunate that so much in Japan is not regulated and defined down to the last detail. So, depending on what you want to impress your counterpart with, you can say that you live in the world's largest metropolis, or that you live outside Tokyo in a small town and in a province that stretches from the mountains to some Pacific islands.

Kamakura

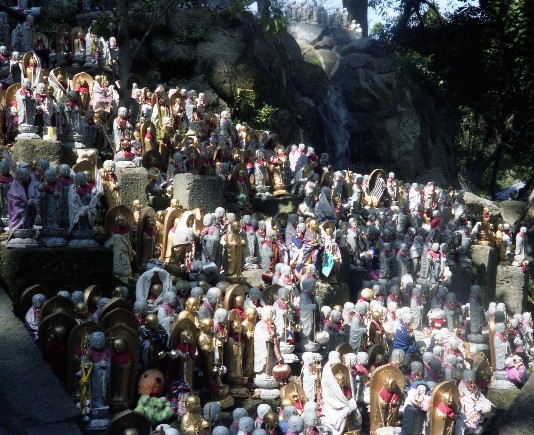

This summer, like almost every year, he took a group of students to Kamakura, just south of Tokyo by the sea. Even if you have been there many times before, it is always amazing how many new things you can discover each time. As well as the Great Buddha, of course, the main focus of the visit was again the Hase Temple, which he always liked to show to the students, because it is a place where very different elements of Japanese religion, including some curiosities, can be found in a colourful mix in one place, forming a remarkably grown unity. Now that he has been visiting the temple regularly for 30 years, he has become increasingly interested in the changes that can be observed there over the years, which allow conclusions to be drawn about changes in Japanese society.

This begins with the attitude of the students, who are less and less interested in the religious elements (even the difference between Buddhism and Shintō has to be explained to some), but are increasingly impressed by the gardens and the magnificent view of the sea that the temple also has to offer. So it is probably no coincidence that each year the gardens there are even more well-tended and beautiful than the year before, as the temple administration has recognised this trend. Another aspect of the temple, however, has receded considerably. It has made the temple known, especially to foreigners, in a way that is obviously not to the temple's liking. This refers to the thousands of small statues of the Bodhisattva Jizō, a kind of patron saint of children, among others, that used to cover the entire slope of the temple. They were erected mainly by women who had lost their child, usually through abortion, and who often continued to care for the little Jizōs in a touching way with little hats, bibs, toys and the like. Apparently in response to numerous publications by foreign and especially American journalists, who saw this as a reflection of the high number of abortions in Japan (and at the same time women's feelings of guilt), but probably also due to social changes, the Jizōs have been decimated year by year and can now only be found lined up grey and expressionless in almost military order near their small temple or banished to the back of the temple complex.

A Shintō shrine, interestingly in the form of a cave complex, is also part of this Buddhist temple. The votive tablets hung near the Torii (the large red entrance gate) reflect an increasing internationalisation and, more recently, politicisation. The former is documented by wishes in many languages (so the Japanese gods are obviously polyglot) and the latter by the pious wish (in English) that the gods prevent Bush from being re-elected.

It is not only in the Hase Temple that one finds this always fascinating diversity and mixture of Buddhist, Shintō and numerous other traditions, and the interweaving of tradition and modernity. One discovers, for example, Ben(zai)ten, the goddess of female beauty, art and wealth (to name but a few of her many functions), who came to Japan with Buddhism, although she has nothing in common with it, and is now worshipped in a Shintō shrine in the precincts of a Zen temple or in the caves of the Hase Temple. The latter even has a nude figure of Benten in its museum, which is unusual for Japan, but it has been removed from display for some years.

In many places, commerce and traditional beliefs are intertwined, for example in the charging of entrance fees that are declared as pilgrimage fees, thus turning foreign tourists into pilgrims and treating devout pilgrims as tourists. He also still remembers the image of the young mother in a kimono, holding her newborn in her arms, presenting her child to the gods in front of the magnificent backdrop of the Hachimangu Shrine, as her ancestors probably did thousands of years ago, and at the same time telling her friend in Tokyo about it, her mobile phone at her ear. You don't have to travel far to discover something new and amazing in Japan.

Distances

When you fly back and forth between Japan and Germany, it's easy to lose sight of the distance between the two countries. Things were different when he first went to Japan in 1970. At the time, the student travel service at his university had a particularly cheap offer for the World Expo in Osaka. The round trip cost a mere DM 670. The route took him from West Berlin by bus to the east of the city, by Interflug to Moscow (including sightseeing and an overnight stay), by domestic Russian flight to Khabarovsk, by train along the Chinese border to Nakhodka and finally a day and a half by ship to Yokohama. In this way, he could and still can better understand the feelings of the first travellers to Japan when, after a long journey, the Japanese islands appeared on the horizon. He also remembers the return journey from the port of Kobe, with the many colourful ribbons that were thrown to the departing passengers and then torn as the ship sailed.

Germany was also far removed from Japan in other ways. Until the 1980s, telephone calls were so expensive that they were only used for urgent messages or short greetings at Christmas. There was no e-mail, of course, so you had to wait two weeks for a letter to be answered. In contrast to today's ubiquitous news from around the world on the Internet, you were lucky to be able to listen to Deutsche Welle on short wave for an hour or two in the evening, depending on the sun's activity. All this has changed almost dramatically. And yet: if you live in both countries alternately for a few weeks, you notice how big the "felt" distance between Japan and Germany still is. And that is a good thing, you might say. Cultures and societies cannot simply be transferred in the form of information data, no matter how extensive. Nor can they be taken with you in a suitcase, at best as souvenirs. Rather, they can live on in you, even in another country, but the environment there remains largely unchanged. He was surprised, for example, at how quickly his interest in the latest sumo results faded when he was in Germany, and how suddenly the results of the German winter athletes became interesting, and vice versa, when he returned to Japan. Of course, this was even more true of political and social events in both countries. In the consciousness of most Germans and Japanese, the other country is hardly present, and if it is, it is often in a strangely distorted form. In his experience, one's own lifestyle and interactions with other people also change significantly depending on which country one lives in, especially if one feels equally at home in both countries. For example, when he makes a phone call from Germany to Japan, he always needs a short period of concentration to switch emotionally to Japan, and yet he usually finds it much harder to adapt to his conversation partner than when he is in Japan, especially if the conversation is conducted in Japanese.