.

Reading Kafka: Vor dem Gesetz (1914)

Before the Law

[The title comes from Kafka. Therefore, just as with Up in the Gallery, for example, it is worth thinking about it for a moment. Kafka could have chosen, for example, "The Doorkeeper (before the Law)". This is indeed how most interpreters see it, who, guided by the man from the country, are completely fixated on the doorkeeper. Kafka's title, however, directs the attention to what is the precondition for the situation described in the text. The expression "before the law" occurs practically only in a single, but all the more important, sentence: Before the law, all are equal. I am sure that Kafka noticed the inner contradiction in this sentence. The law is supposed to guarantee the equality of all. But if all are before the law, then they are outside and thus excluded from the law. More poignantly, they are in a realm where power and arbitrariness rule instead of law and justice. This can be seen in the relationship between the man from the country and the doorkeeper. The reason for this is also apparent in the "before". The law is presented as a higher power, like a king on his throne, which is expressed even today in many courtrooms by the elevated seat of the judge].

Vor dem Gesetz steht ein Türhüter.

Before the Law stands a Doorkeeper.

[In terms of form, this is an objective statement as a starting point for what follows. In the context of the next sentences, however, it is clear that this is the inner view of the man from the country, his view of the world. He does not see the law as a space in the figurative sense, an area in which everyone is equally protected by the law, but rather imagines it in concrete spatial terms, like a respect-inspiring courthouse, where the doorkeeper then fits in].

Zu diesem Türhüter kommt ein Mann vom Lande und bittet um Eintritt in das Gesetz.

To this doorkeeper comes a man from the countryside asking to enter the law.

[Instead of simply entering or just asking the doorkeeper whether he is in the right place, the man from the countryside obviously has so much respect and is probably also afraid that he asks the doorkeeper to enter. In doing so, he delegates to the doorkeeper an authority of which it is not at all clear whether it exists at all outside the man's sphere of imagination. Is it the feudalistic ideas in his head, the acceptance of authoritarian structures, that make him do this?]

Aber der Türhüter sagt, daß er ihm jetzt den Eintritt nicht gewähren könne. Der Mann überlegt und fragt dann, ob er also später werde eintreten dürfen. "Es ist möglich", sagt der Türhüter, "jetzt aber nicht."

But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant him entry now. The man thinks about it and then asks whether he will be allowed to enter later. "It is possible," says the doorkeeper, "but not now."

[The doorkeeper immediately tests the extent of his power over the man and denies him entry. At the same time he stalls him with the "not now" and the vague "it is possible". In this way he secures his continued control over the man. The man's question shows that this works. At first he "thinks about it". Here one might have expected a critical consideration that questions the situation as a whole, but at this point the consideration probably means only a brief hesitation].

Da das Tor zum Gesetz offensteht wie immer und der Türhüter beiseite tritt, bückt sich der Mann, um durch das Tor in das Innere zu sehn. Als der Türhüter das merkt, lacht er und sagt: ""Wenn es dich so lockt, versuche es doch, trotz meines Verbotes hineinzugehn. Merke aber: Ich bin mächtig. Und ich bin nur der unterste Türhüter. Von Saal zu Saal stehn aber Türhüter, einer mächtiger als der andere. Schon den Anblick des dritten kann nicht einmal ich mehr ertragen."""

As the gate to the law is open as always and the doorkeeper steps aside, the man stoops to peer through the gate into the interior. When the doorkeeper notices this, he laughs and says: "If you are so tempted, try to go in despite my prohibition. But remember: I am powerful. And I am only the lowest doorkeeper. But from hall to hall stand doorkeepers, one mightier than the other. Even I cannot bear the sight of the third."

[This clearly shows how much the doorkeeper's power has now grown. He can afford to step aside and mockingly ask the man to come in. The man's stooped posture shows his submissiveness. The fact that the doorkeeper can speak of "my prohibition" and call himself "powerful", and that the other doorkeepers are also only concerned with power based on fear, makes it clear how much we find ourselves here outside the law in a world of authoritarian powers. All this, of course, from the inside view of the man from the countryside. And how much all this should belong to a time long gone is made clear by the motif familiar from fairy tales of the "doorkeepers, one mightier than the other"].

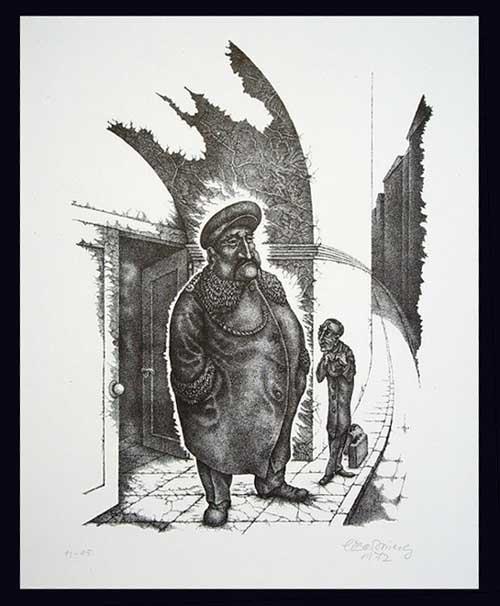

Solche Schwierigkeiten hat der Mann vom Lande nicht erwartet; das Gesetz soll doch jedem und immer zugänglich sein, denkt er, aber als er jetzt den Türhüter in seinem Pelzmantel genauer ansieht, seine große Spitznase, den langen, dünnen, schwarzen tatarischen Bart, entschließßt er sich, doch lieber zu warten, bis er die Erlaubnis zum Eintritt bekommt.

The man from the countryside did not expect such difficulties; the law should be accessible to everyone and always, he thinks, but when he now takes a closer look at the doorkeeper in his fur coat, his big pointed nose, the long, thin, black Tatar beard, he decides that he would rather wait until he gets permission to enter.

[With the word "difficulties" the man tries to play down his hopeless situation. But the timid attempt to think and invoke his right to do so is stifled by fear of what he sees as the fearsome figure of the doorkeeper].

Der Türhüter gibt ihm einen Schemel und läßßt ihn seitwärts von der Tür sich niedersetzen. Dort sitzt er Tage und Jahre. Er macht viele Versuche, eingelassen zu werden, und ermüdet den Türhüter durch seine Bitten.

The doorkeeper gives him a stool and makes him sit down at the side of the door. There he sits for days and years. He makes many attempts to be let in, and wearies the doorkeeper with his entreaties.

[The doorkeeper is now so much in control of the man that he can grant him a few small comforts. The man is apparently no longer able to escape this control and so years pass. How dependent he is is also shown by his feelings of guilt towards the doorkeeper ("wearies the doorkeeper")].

Der Türhüter stellt öfters kleine Verhöre mit ihm an, fragt ihn über seine Heimat aus und nach vielem andern, es sind aber teilnahmslose Fragen, wie sie großße Herren stellen, und zum Schlusse sagt er ihm immer wieder, daßß er ihn noch nicht einlassen könne.

The doorkeeper often interrogates him, asks him about his home and many other things, but they are impassive questions like those asked by great lords, and in the end he always tells him that he cannot let him in yet.

[Here we have finally entered a kind of feudal society in the man's imagination: "great lords", "interrogations", "impassive questions". The "not yet" proves to be a lie at the end at the latest, with which the doorkeeper wants to bind the man to himself].

Der Mann, der sich für seine Reise mit vielem ausgerüstet hat, verwendet alles, und sei es noch so wertvoll, um den Türhüter zu bestechen. Dieser nimmt zwar alles an, aber sagt dabei: ""Ich nehme es nur an, damit du nicht glaubst, etwas versäumt zu haben.""

The man, who has equipped himself with many things for his journey, uses everything, no matter how valuable, to bribe the doorkeeper. The latter accepts everything, but says: "I only accept it so that you will not think you have missed anything."

[Here the man, who actually strives for the law, now also enters the sphere of lawlessness himself by trying to bribe the doorkeeper].

Während der vielen Jahre beobachtet der Mann den Türhüter fast ununterbrochen. Er vergißßt die andern Türhüter und dieser erste scheint ihm das einzige Hindernis für den Eintritt in das Gesetz. Er verflucht den unglücklichen Zufall, in den ersten Jahren rücksichtslos und laut, später, als er alt wird, brummt er nur noch vor sich hin. Er wird kindisch, und, da er in dem jahrelangen Studium des Türhüters auch die Flöhe in seinem Pelzkragen erkannt hat, bittet er auch die Flöhe, ihm zu helfen und den Türhüter umzustimmen.

During the many years, the man watches the doorkeeper almost continuously. He forgets the other doorkeepers and this first one seems to him the only obstacle to entering the law. He curses the unfortunate coincidence, in the first years recklessly and loudly, later, as he grows old, he only grumbles to himself. He becomes childish, and, having also recognised the fleas in the doorkeeper's fur collar in his years of study, he also asks the fleas to help him and change the doorkeeper's mind.

[By fixating on the doorkeeper, the man's world narrows more and more and he eventually becomes childish. With almost sarcastic irony, the end of a failed life is described here, with the narrator slowly detaching himself from the man's inner view].

Schließßlich wird sein Augenlicht schwach, und er weißß nicht, ob es um ihn wirklich dunkler wird, oder ob ihn nur seine Augen täuschen. Wohl aber erkennt er jetzt im Dunkel einen Glanz, der unverlöschlich aus der Türe des Gesetzes bricht. Nun lebt er nicht mehr lange.

Finally, his eyesight grows dim, and he does not know whether it is really getting darker around him, or whether his eyes are only deceiving him. But now he recognises in the darkness a radiance that inextinguishably breaks out of the door of the law. Now he does not live much longer.

[Shortly before his death, when he can no longer trust his eyes, he nevertheless believes he can recognise a supernatural, imagined radiance from the door of the law, a vision that obviously springs from his longing for the law. In the external view, this increases the doubts about his state of mind, unless one believes in the possibility of a special illumination in the phase of death].

Vor seinem Tode sammeln sich in seinem Kopfe alle Erfahrungen der ganzen Zeit zu einer Frage, die er bisher an den Türhüter noch nicht gestellt hat. Er winkt ihm zu, da er seinen erstarrenden Körper nicht mehr aufrichten kann. Der Türhüter muß sich tief zu ihm hinunterneigen, denn der Größßenunterschied hat sich sehr zu ungunsten des Mannes verändert. ""Was willst du denn jetzt noch wissen"?" fragt der Türhüter, ""du bist unersättlich."" ""Alle streben doch nach dem Gesetz", sagt der Mann, "wieso kommt es, daßß in den vielen Jahren niemand außßer mir Einlaßß verlangt hat?"?"

Before his death, all the experiences of the whole time gather in his head to form a question which he has not yet put to the doorkeeper. He beckons to him because he can no longer raise his stiffening body. The doorkeeper has to lean low towards him, for the difference in height has changed much to the man's disadvantage. "What do you want to know now?" asks the doorkeeper, "you are insatiable." "Everyone strives for the law," says the man, "why is it that in all these years no one but me has asked for admittance?"

[Just when his body is already stiffening, a question comes from the man after all, which of course he should have asked long before. The answer is then something like the death blow for him].

Der Türhüter erkennt, daßß der Mann schon an seinem Ende ist, und, um sein vergehendes Gehör noch zu erreichen, brüllt er ihn an: ""Hier konnte niemand sonst Einlaßß erhalten, denn dieser Eingang war nur für dich bestimmt. Ich gehe jetzt und schließße ihn.""

The doorkeeper realises that the man is already at the brink of his end and, in order to reach his fading hearing, he shouts at him: "No one else could gain entry here, for this entrance was intended only for you. I am leaving now and closing it."

[Everyone has his/her own access to the law. You can only gain it for yourself, but you can also block it for yourself, like the man from the country. Is that what Kafka is saying here? In any case, in order to gain access, one must free oneself from feudalistic and authoritarian thought structures and must critically and fearlessly recognise one's own possibilities. Above all, one must not shift responsibility onto others like the man from the countryside, but rather act responsibly oneself. Is that, in very simplified terms, the " moral of the story"? In any case, it is worth thinking about].