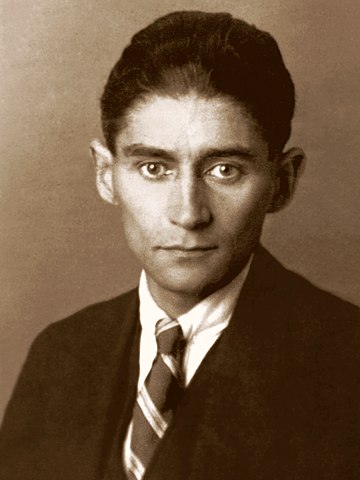

Franz Kafka was 40 years old when he died in 1924, a year after the above photograph was taken. At the time, few people knew and appreciated him. Today, 100 years later, people all over the world are fascinated by his works and the literature on him is immense.

Kafka's difficult relationship with his father is well known. He felt almost crushed by his overbearing personality. His relationships with women also added pressure and complications. He was engaged three times to Felice, then her friend Grete followed, then his great love Milena, and finally a reconciliatory end with Dora. He found the greatest support in his sister Ottla. They helped each other to get out of their father's spell. This is just a small indication of the immense complexity of Kafka's inner life. But we should leave the mysteries of his life, which Kafka himself could not solve, as they are. The insights that Kafka gained he tried to express in his texts. We should stick to them.

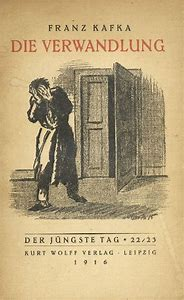

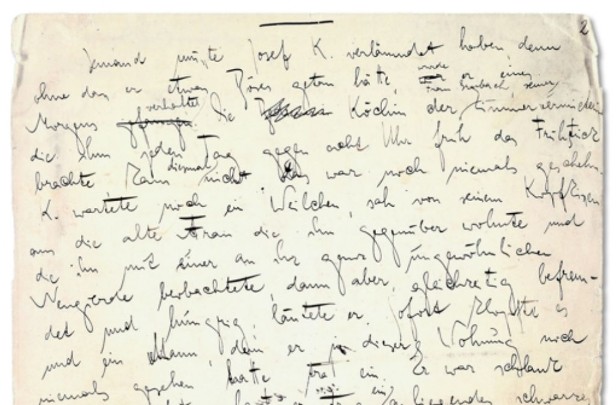

Kafka's willingness to sacrifice everything else in order to give literary expression to the "enormous world" and the "dreamlike life" he felt within himself impresses people to this day. But the texts are not easy to understand. Kafka created an entirely new kind of literature to free himself from the constraints and prejudices of traditional language. Only gradually is it dawning on many that what he describes is not a grotesque, absurd, or even "Kafkaesque" world, but that he makes visible an inner truth that is obscured by our attachment to conventional thinking. (more details)

I only gradually realised how important my move to a university in Japan and the decades of new experiences there were for my understanding of Kafka's texts. Kafka knew almost nothing about Japan. How could he describe things that are very much alive in Japanese language and culture, but largely unknown and misunderstood in Europe? But isn't that what art and the artist are all about, the ability to make visible deep, inner, universal truths that are often not even present in the traditional world of imagination and its language?

Something of this, I think, is felt by every reader of Kafka's texts, and it is this fascination that leads one to engage with him again and again. And how much it is worthwhile to dream with Kafka, to discover the "dreamlike inner life" in his texts, is something I have in fact often experienced and would now like to try to convey here.

The numerous examples of Amae in Kafka's texts are particularly astonishing. In addition to some life testimonies, this applies above all to The Metamorphosis and Josefine, the Singer or The Mouse Folk.

It is about a special form of emotional dependence. This is still largely absent in the world of German language and culture, but was nevertheless recognised and comprehensively described by Kafka as an important element in human relationships. It is explored here in a roundabout way via the Japanese language and culture, where it is known as Amae.

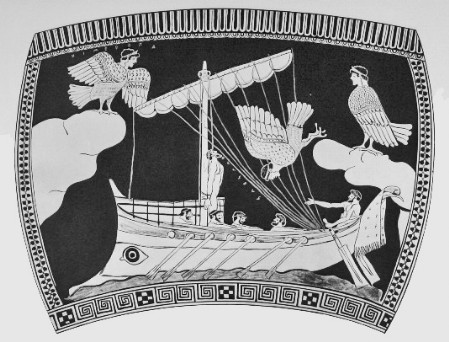

Since time immemorial, human dreams have found expression in myths and legends. Kafka draws on this in some of his short stories, such as Prometheus or The Silence of the Sirens, radically questioning the traditions leading to European modernity, with echoes of traditions also found in Japan.

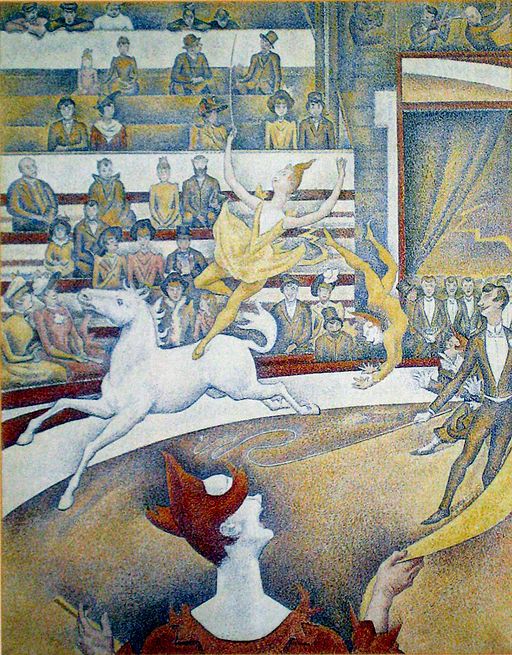

Particularly important for understanding Kafka's world is his short, very dense text Up in the Gallery, for which I have therefore written a separate introduction. A similar problem is addressed in the short text Der Kreisel.

Finally, a particularly original expression of Kafka's "world in his head" and his "dreamlike inner life" can be found in The Bridge, a playing with the limits and possibilities of being human.

Still under construction is a section that attempts to accompany the reading of some of Kafka's texts with a parallel interpretation.