.

Reading Kafka: Auf der Galerie (1917)

Up in the Gallery

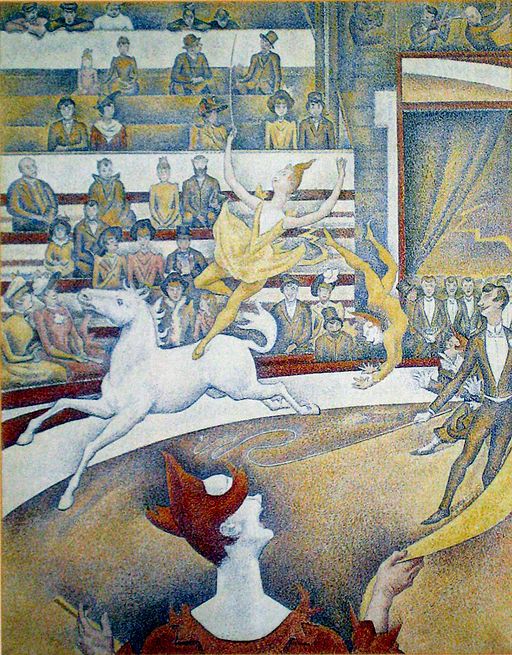

[This short prose piece consists of only two long sentences, whic apparently form a contrast. Here, every word deserves individual consideration. It begins with the title. Kafka may have been inspired to write the text by the adjacent painting by Seurat. In terms of content, it corresponds to it in many details. But then why doesn't Kafka also call it "The Circus", but instead "Up in the Gallery", i.e. what you can just see at the top of Seurat's painting? Apparently, he is not primarily concerned with what happens in the circus ring, but with what happens in the gallery, namely with the attitude of the young man there, who reacts in two different ways to what happens in the ring].

[Franz Kafka: Sämtliche Erzählungen. Hrsg. von P. Raabe. Frankfurt 1970, S. 129] [see]

Wenn irgendeine hinfällige, lungensüchtige Kunstreiterin in der Manege auf schwankendem Pferd vor einem unermüdlichen Publikum vom peitschenschwingenden erbarmungslosen Chef monatelang ohne Unterbrechung im Kreise rundum getrieben würde,

If some frail, consumptive equestrienne were to be driven round and round in the ring on a swaying horse in front of a tireless audience by the whip-wielding, merciless boss for months without interruption,

[The first sentence is a "What if?" style consideration. It is a rational reflection in which the conditions for a certain action are shown. Specifically, it is about a case of blatant exploitation in a circus. It is a model case of social accusation, which is already evident from the fact that it is not about a specific person, but about "some" artist. In the process, the situation is presented as extremely outrageous: a sick woman who is "driven round and round" by the audience and the "whip-wielding merciless boss." Whereby the imagination with the "for months without interruption" almost escalates into the irrational].

auf dem Pferde schwirrend, Küsse werfend, in der Taille sich wiegend,

whirling on the horse, throwing kisses, swaying at the waist,

[Here this escalation is taken back a bit in the direction of the reality of the circus as we know it].

und wenn dieses Spiel unter dem nichtaussetzenden Brausen des Orchesters und der Ventilatoren in die immerfort weiter sich öffnende graue Zukunft sich fortsetzte, begleitet vom vergehenden und neu anschwellenden Beifallsklatschen der Hände, die eigentlich Dampfhämmer sind -

and if this play were to continue into the ever-widening grey future to the never-ending roar of the orchestra and the fans, accompanied by the fading and re-swelling applause of the hands that are actually steam hammers -

[But only to escalate again into an almost apocalyptic vision. The "play" could be linked to the idea of playfulness that is associated with the circus. In view of the following description, however, it is more reminiscent of the cruel game being played with the artist. At the end of the "If"-clause, there should actually be a clearly recognisable situation that enables appropriate action. Instead, things (like the music of the orchestra and the sound of the fans) blend and dissolve into a "grey future" of hopelessness. Eventually, the reflective consciousness is so confused that it mistakes its own made-up conditions for reality and believes that the hands actually "are" steam hammers].

vielleicht eilte dann ein junger Galeriebesucher die lange Treppe durch alle Ränge hinab, stürzte in die Manege, rief das: Halt!! durch die Fanfaren des immer sich anpassenden Orchesters.

Perhaps a young gallery visitor would then rush down the long staircase through all the tiers, rush into the ring, shout the - Stop!! through the fanfares of the ever-adjusting orchestra.

[A reaction is apparently most likely to come from a young visitor up in the gallery. But the long walk to the ring and the fanfares that seek to drown out this disturbance leave little hope. The situation seems even more hopeless when the first sentence as a whole is analysed in a critical-rational way, in the attitude suggested by the "What if?" structure of this sentence. Here, the "perhaps" at the beginning of the main clause becomes important. If, in view of the assumed situation of extreme exploitation and inhumanity, the gallery visitor's reaction occurs only "maybe", then this can only be understood as an expression of complete hopelessness. What even worse situation would one have to imagine for people to be roused to a counter-reaction?

But one can also read the text differently. If one allows oneself to be carried along by the intensity of the feelings and the dismay of the gallery visitor towards the fate of the circus artist, starting with his almost sentimental feelings ("frail, consumptive") up to the almost apocalyptic visions, then the "perhaps" can even become an expression of great hope (see, before note 30)].

Da es aber nicht so ist; eine schöne Dame, weißss und rot, hereinfliegt, zwischen den Vorhängen, welche die stolzen Livrierten vor ihr öffnen;;

But since it is not so, a beautiful lady, white and red, flies in between the curtains that the proud men in liveries open before her;

[Be that as it may, at the beginning of the second sentence it is clearly stated that it is not so. However, it remains unclear what is meant by the "so". This also leaves open at this point how it is in reality. That is now described in detail in the following. In terms of sentence structure, what follows is a long series of subordinate clauses (each separated by a semicolon), which should actually all begin with "since" and which give the reason for the gallery visitor's reaction at the end. But this "since" is omitted and so the individual sentences appear almost like a sequence of independent observations. Only the final position of the verb (in German!) continues to make their subordination as subordinate clauses clear (if one notices them at all). Here, even within a sentence, the individual elements dissolve into a sequence of independent individual observations. First, a beautiful lady catches the eye, then two colours particularly strike the eye, although it remains unclear what they refer to. Then attention is directed to the flying in and only afterwards is it registered what preceded it all, the curtains and the opening by the liveried men. The fact that these are called "proud" is a first small hint that we remain quite aware that this is a show with a lot of false pretences].

der Direktor, hingebungsvoll ihre Augen suchend, in Tierhaltung ihr entgegenatmet;; vorsorglich sie auf den Apfelschimmel hebt, als wäre sie seine über alles geliebte Enkelin, die sich auf gefährliche Fahrt begibt; sich nicht entschliessßen kann, das Peitschenzeichen zu geben;;

the director, devoutly seeking her eyes, breathes towards her in an animal posture; lifts her precautiously on the apple-white horse, as if she were his beloved granddaughter about to go for a dangerous ride; cannot make up his mind to give the whip signal;

[This becomes even clearer in the description of the director. The exaggerations and the show-like in his behaviour are clear. At the same time, however, the word " precautiously" ("vorsorglich") is used in a clever way to point out that the reality behind the beautiful appearance could be quite different. This is revealed by a linguistic-critical consideration. In the context of the beautiful appearance, "caringly" (fürsorglich") should actually be written here. This can easily be overlooked, since the meaning is not that different. But "precautionary" is used for measures that are supposed to prevent a problem in the future. Maybe the director is worried that the artist will get scared at the last moment or even protest against her treatment. This is only implied, not considered further, but the possible ambiguity of it all remains in mind].

schliessßlich in Selbstüberwindung es knallend gibt;; neben dem Pferde mit offenem Munde einherläuft;; die Sprünge der Reiterin scharfen Blickes verfolgt;; ihre Kunstfertigkeit kaum begreifen kann;; mit englischen Ausrufen zu warnen versucht; die reifenhaltenden Reitknechte wütend zu peinlichster Achtsamkeit ermahnt; vor dem grossßen Salto mortale das Orchester mit aufgehobenen Händen beschwört, es möge schweigen;;

finally, in self-conquest, gives it with a bang; runs along beside the horse with his mouth open; follows the rider's jumps with a sharp eye; can hardly comprehend her artistry; tries to warn with English exclamations; angrily admonishes the tyre-holding grooms to the most scrupulous attentiveness; before the great salto mortale, implores the orchestra with raised hands to be silent;

[Also when the director gives the whip sign "with a bang", one senses the contrast to his played "in self-conquest". As before, the subject is missing in the following clauses, not even a "he" refers to the director. Here, too, the individual observations become independent, much remains in limbo, the logical framework recedes. Again, a possible ambiguity is indicated by expressions such as "follows ... with a sharp eye", "with English exclamations" or "angrily"].

schließsslich die Kleine vom zitternden Pferde hebt, auf beide Backen küssßt und keine Huldigung des Publikums für genügend erachtet; während sie selbst, von ihm gestützt, hoch auf den Fußßspitzen, vom Staub umweht, mit ausgebreiteten Armen, zurückgelehntem Köpfchen ihr Glück mit dem ganzen Zirkus teilen will -

finally, lifts the girl from the trembling horse, kisses her on both cheeks and does not consider any homage from the audience to be sufficient; while she herself, supported by him, high on her toes, blown by the dust, with outstretched arms, her little head leaning back, wants to share her happiness with the whole circus -

[Here the action in the ring reaches its climax and with it the enthusiasm of the audience. Only the "dust" somewhat clouds the beautiful final image of the artist who "wants to share her happiness with the whole circus". How is the reaction of the gallery visitor to be understood]?

da dies so ist, legt der Galeriebesucher das Gesicht auf die Brüstung und, im Schlussmarsch wie in einem schweren Traum versinkend, weint er, ohne es zu wissen.

since this is so, the visitor to the gallery puts his face on the parapet and, sinking into the final march as in a heavy dream, weeps without knowing it.

[By appending the previous clause with "while", the logical structure of the entire second sentence has receded even further. It doesn't help that the "since", which has been omitted throughout, is now taken up again. Especially because it remains unclear what both the "this" and the "so" refer to. Perhaps one can say: This, what could be observed in detail, is just the way it is. That is all that can be said.

The attitude in the second sentence is characterised by accepting reality as it is and by passively taking in the images, which are juxtaposed impressionistically, without logical connection. Possible contradictions to the beautiful appearance of the circus are certainly suspected and sensed, but remain in abeyance. Even the weeping at the end remains undetermined in its negative or positive implications; it shows a deep, emotionally determined relationship to reality, which, however, in its indeterminacy cannot form a basis for responsible action. The gallery visitor absorbs the phenomena as a whole, intuitively senses their complexity and is thus very close to reality, but at the same time he loses the consciousness of himself and thus the possibility to act].

Appendix

This was only a first reading of the text. It is worth reading it several times, because many connections and nuances only gradually become apparent. The text shows how our understanding of reality and our actions change depending on whether our attitude is (roughly speaking) more critically rational or emotionally determined. It is particularly fascinating to see how this also applies to our understanding of this text, as shown above with the examples of "perhaps" and "precautiosly".