.

.

-

Home-Coming (1923)

The title was added posthumously at the time of publication. It is inappropriate because it is noticeable that in Kafka's text this very word is avoided. This is reminiscent of Thomas Mann's Tonio Kröger (1903), where the protagonist also initially talks awkwardly around the fact that he wants to visit his hometown, thus trying to suppress the feelings associated with the word 'home'.

[Franz Kafka: Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente II, S. 572f (1920)] [siehe] [transation by Tania and James Stern]

Ich bin zurückgekehrt, ich habe den Flur durchschritten und blicke mich um.

I have returned, I have passed under the arch and am looking around.

[The first emotionless, sober words do not suggest that this could be a return home, especially since it is not said at first where the return is taking place. The rest of the sentence rather suggests someone who is advancing on hostile terrain and then looks around to get his bearings].

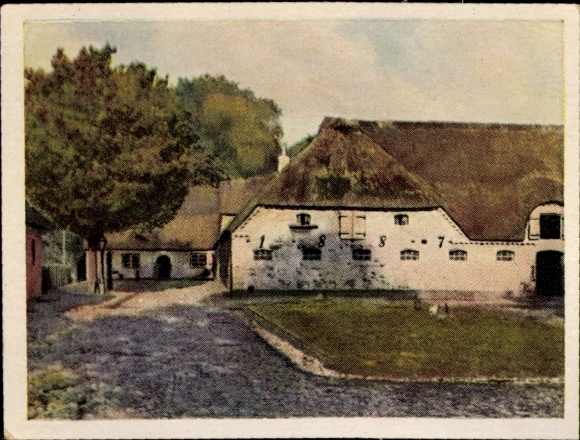

Es ist meines Vaters alter Hof. Die Pfütze in der Mitte. Altes unbrauchbares Gerät in einander verfahren verstellt den Weg zur Bodentreppe.

It's my father's old yard. The puddle in the middle. Old, useless tools, jumbled together, block the way to the attic stairs.

[Then the destination of the return is mentioned, but not as 'our farm' or at least 'my father's house', as one might expect. In connection with these emotionally positive phrases, the 'old' would also sound positive in the sense of 'familiar': 'our (good) old farm'. So it sounds rather negative, as a past associated with the father and seeming to concern only him. The puddle and the 'old useless tools jumbled together' that obstruct the way also fit this negative impression. But one should also not forget that both belong to a farm and should thus arouse homey feelings in a farmer's son, especially in the memory of childhood days when he surely played with joy in the puddle or hid in the attic. The fact that the way to the attic stairs is blocked can really only be relevant with regard to such childhood memories, while the adult son is already standing in front of the kitchen door. The stringing together of negative terms here therefore seems rather to reflect his inner situation, including the effort to prevent other positive memories from arising in the first place].

Die Katze lauert auf dem Geländer. Ein zerrissenes Tuch einmal im Spiel um eine Stange gewunden hebt sich im Wind.

The cat lurks on the banister. A torn piece of cloth, once wound around a stick in a game, flutters in the breeze.

[Something similar applies to the next two sentences. The cat may simply be crouching on the railing. But for him it lurks and thus seems part of an environment that is alien or even hostile to him. In any case, it gives no sign that it welcomes him. That he is actually expecting a sign of welcome could be suggested by the cloth that rises in the breeze. But it is not a cloth that is waved to welcome him, torn moreover. All the same, the word "play" here refers directly to childhood, perhaps even a concrete memory, but the indefinite wording avoids any reference to concrete persons].

Ich bin angekommen. Wer wird mich empfangen? Wer wartet hinter der Tür der Küche?

I have arrived. Who is going to receive me? Who is waiting behind the kitchen door?

[Once again, he soberly states that he has arrived at his destination, again he does not name it and only speaks of "arrived". But then he cannot avoid thinking of the people he will meet there, the "receive" giving the impression that it is not a matter of personal relations. Still he hesitates. The person who is glad to be back home does not wonder who is behind the door of the kitchen, but simply opens it. The way the sentence is worded, one has the feeling that he may even be afraid of what is waiting for him behind the door].

Rauch kommt aus dem Schornstein, der Kaffee zum Abendessen wird gekocht. Ist Dir heimlich, fühlst Du Dich zuhause?

Smoke is rising from the chimney, coffee is being made for supper. Do you feel you belong, do you feel at home?

[Here we now have the greatest emotional approach to the relatives presumed in the kitchen and the family atmosphere there. The first sentence evokes a typical situation in which one particularly enjoys returning home, for example in the evening after working in the fields or after a journey. This is also where the words "feel you belong" and "feel at home" first appear to describe this emotion. Kafka uses "heimlich," as in his environment, in the sense of homely, but the other meaning ("secretely") also resonates and is taken up twice at the end with the word "secret". The fact that he wonders whether this feeling is there shows that he obviously does not feel it spontaneously, but probably misses it. It could also be an attempt to suppress an emerging feeling of this kind by questioning it. The questions show that he leaves the hitherto subliminal level of feeling and tries to analyse the situation rationally and critically].

Ich weiss es nicht, ich bin sehr unsicher.

I don't know, I feel most uncertain.

[This begins with the admission of his ignorance. The uncertainty, which was already clearly noticeable up to now, is now briefly and concisely addressed directly here and even reinforced by "most"].

Meines Vaters Haus ist es, aber kalt steht Stück neben Stück als wäre jedes mit seinen eigenen Angelegenheiten beschäftigt, die ich teils vergessen habe teils niemals kannte. Was kann ich ihnen nützen, was bin ich ihnen und sei ich auch des Vaters, des alten Landwirts Sohn.

My father's house it is, but each object stands cold beside the next, as though preoccupied with its own affairs, which I have partly forgotten, partly never known. What use can I be to them, what do I mean to them, even though I am the son of my father, the old farmer?

[The reference to the father forms the framework for the next two sentences. Thinking of Kafka's father is not very helpful here, as is so often the case when Kafka's biographical data are used for interpretation. There is nothing here of Kafka's extremely complex relationship with his father. As it is presented here, the father appears, so to speak, only in his function as part of the family history, especially at the end where the "old farmer" is mentioned, rather like someone we only know from old family photos. There is no sense of an emotional connection. This is matched by the "cold" at the beginning and the descriptions that follow, where the emotional ties to the family and familiar surroundings that normally result from the father-son relationship are completely absent, but apparently missed, as the "but" at the beginning and especially the "even though" at the end of the description show. Human relationships are so "cold" that they seem almost like objects (cf. the quotation at the end), to which the "What use can I be to them" fits, too. One can also hear a self-reproach. After all, the question "what do I mean to them" implies that people can and should mean something to each other].

Und ich wage nicht an der Küchentür zu klopfen, nur von der Ferne horche ich, nur von der Ferne horche ich stehend, nicht so dass ich als Horcher überrascht werden könnte. Und weil ich von der Ferne horche, erhorche ich nichts, nur einen leichten Uhrenschlag höre ich oder glaube ihn vielleicht nur zu hören herüber aus den Kindertagen.

And I don't dare knock at the kitchen door, I only listen from a distance, I only listen from a distance, standing up, in such a way that I cannot be taken by surprise as an eavesdropper. And since I am listening from a distance, I hear nothing but a faint striking of the clock passing over from childhood days, but perhaps I only think I hear it.

[In this situation he does not even dare to knock on the kitchen door. How far he is already inwardly away is made clear by the triple "from a distance" and by the fact that he listens like a stranger, "standing up", ready to flee at any moment. There is still something that connects him to his childhood days, but only like a "faint striking of the clock" that you are not sure you really heard].

Was sonst in der Küche geschieht ist das Geheimnis der dort Sitzenden, das sie vor mir wahren.

Whatever else is going on in the kitchen is the secret of those sitting there, a secret they are keeping from me.

[Here the other meaning associated with the word 'Heim(at)' becomes apparent. Besides 'homely', 'heimlich' also includes 'secret', in other words the phenomena of demarcation, seclusion and self-interests].

Je länger man vor der Tür zögert, desto fremder wird man. Wie wäre es wenn jetzt jemand die Tür öffnete und mich etwas fragte. Wäre ich dann nicht selbst wie einer der sein Geheimnis wahren will.

The longer one hesitates before the door, the more estranged one becomes. What would happen if someone were to open the door now and ask me a question? Would not I myself then behave like one who wants to keep his secret?

[Now he has moved so far away from his personal feelings that he can formulate his experience here as a general human experience. Even if something like a vague hope seems to germinate once again in the sense of 'How would it be if', the rest of the sentence shows that it is about a very sober consideration in the sense of "What would happen if.° And the fact that someone comes and asks him something no longer has anything to do with an emotional encounter with the family that is actually to be expected in his situation. The last sentence then shows what he has been primarily concerned with all along: the preservation of his own against the (emotional) demands of the family, of the community.

The relationship between the individual and the community was a lifelong preoccupation of Kafka. It is still a central theme in his last work, Josefine.... In connection with our text, the following quotations from his diaries are particularly revealing. On 29 October 1921, he writes that after many refusals, he did once join the family's evening card game and then says:

But it did not result in any closeness [...] That is how it would always have been. I have only very rarely crossed this borderland between solitude and community, I have even settled more in it than in solitude itself. What a lively, beautiful country Robinson's Island was in comparison.

[...]

What connects you more closely with these fixed, speaking, eye-flashing bodies than with any thing, such as the pen in your hand? That you are of their kind? But you are not of their kind, which is why you raised this question. The fixed delimitation of human bodies is ghastly.

[Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente II: S. 871f.]